Itron Rohan

La Dame de Rohan

The Lady Rohan

Chant tiré du 2ème Carnet de collecte de La Villemarqué (pp. 285 - 285 bis).

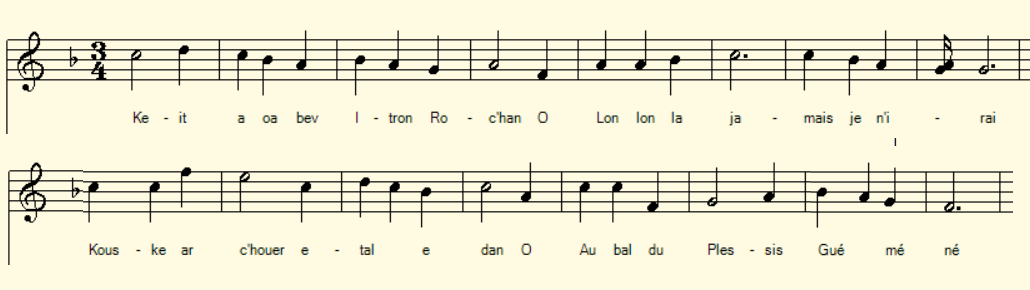

Mélodie

Arrangement Christian Souchon (c) 2021

|

A propos de la mélodie Inconnue. Pourtant le manuscrit fournit des précisions détaillées à ce sujet: "Cf. la chanson française: "Lonlonla, jamais je n'irai / Au bal du Plessis Guéméné". On peut penser à la marche des "Dragons de Noailles", une chanson de 1666 dont le couplet unique, noté dans un manuscrit datant de 1765/1766 fait allusion à la blessure du Maréchal de Chevreuse: "Lonlonla, j'ai le nez cassé / Je n'irai plus dans la tranchée. Lonlonla, j'ai le nez cassé / Je m'en vas me faire panser." (Source: "Trois chansons inédites du temps des trois Louis, 1610 - 1774" de Henri Bellugou, 1975, p. 59). On peut aussi comprendre que ce passage "lonlonla etc." est utilisé comme refrain alterné en français dans le chamt breton, comme cela arrive parfois. C'est ce que nous avons supposé en prenant pour accompagner le présent chant, à titre d'illustration, l'air "Tu croyais en aimant Colette" tiré de l'"Almanach chantant" Bibliothèque historique le la ville de Paris n°601664: "Clé du Caveau" N° 574. Cependant La Villemarqué a noté ce qui semble être le titre d'une mélodie : "Frettoù aour an Dukez Ana" . Nous proposons de traduire "Les ferrets (= aiguillettes) d'or de la Duchesse Anne", sachant que le feuiileton "Les trois mousquetaires" d'Alexandre Dumas, a débuté dans le "Siècle" en mars 1844. A propos du texte Querelle du Barzhaz oblige, La Villemarqué note précisément la date de collecte de ce chant 28 août 1882, les noms des chanteurs, un jeune homme, Ronan Ristual et un vieillard Jacques Collober, ainsi que le lieu, Rédéné, entre Quimperlé et Lorient. Peut-être la phrase "Le bal du Plessis-Guéméné" est elle un argument en la faveur d'une origine locale de cette chanson: un peu plus de 30 km séparent Rédéné de Guéméné du Scorff. Malgré l'isolement auquel il s'était condamné, semble-t-il, La Villemarqué conservait apparemment des relations suivies avec quelques personnalités telles que l'historien breton Arthur Le Moyne de La Borderie (qui mourut en 1907). Un chant historique Celui-ci confirme le caractère historique de ce chant: un démélé sanglant entre deux époux issus de deux branches différentes de la noble famille des Rohan. La remarque selon laquelle certains Rohan étaient impopulaires fait peut-être écho à l'expression citée à propos du Siège de Guingamp: "Debriñ en nev evel ma ra Roc'han" (Il mange à l'auge comme Rohan= il vit en parasite) ou à l'expression "mab Roc'han" (fils de Rohan) qui désigne un porc, selon une remarque consignée dans la "Revue Celtique" T. III, p.209 (1876-1878). |

About the melody Unknown. However the manuscript provides details on this subject: "Cf. the French song:" Lonlonla, never I will not go / At the ball of Plessis Guéméné ". We can think of the march of the "Dragons de Noailles", a song from 1666 whose unique stanza, noted in a manuscript dating from 1765 / 1766 alludes to the injury of Maréchal de Chevreuse: "Lonlonla, my nose is broken / I won't go into the trench again. Lonlonla, my nose is broken / I'm going to get a bandage. " (Source: "Three unpublished songs from the time of the three Louis, 1610 - 1774" by Henri Bellugou, 1975, p. 59). We can also understand that this passage "lonlonla etc." is used as an alternating refrain in French in a Breton song, as sometimes happens. This is what we assumed by taking to accompany the present song, by way of illustration, the air "You believed, if you loved Colette" taken from the "Almanac chantant" (Bibliothèque historique le la ville de Paris n ° 601664): "Clé du Caveau" N ° 574. However La Villemarqué noted what seems to be the title of a melody: "Frettoù aour an Dukez Ana". We propose to translate " Duchess Anne's gold aglets", knowing that the publication of the serialized novel "The three musketeers" by Alexandre Dumas, began in the review "Le Siècle" in March 1844. About the lyrics As a result of the "Barzhaz quarrel", La Villemarqué notes precisely for this song, the date of collection : August 28, 1882, the names of the singers: a young man, Ronan Ristual and a very old man Jacques Collober, as well as the place: Rédéné, between Quimperlé and Lorient. br> Perhaps the burden "Le bal du Plessis-Guéméné" hints at a local origin of this song, since hardly more than 30 km separate Rédéné from Guéméné on Scorff. Despite the isolation to which he is said to have condemned himself, La Villemarqué apparently maintained close relations with some personalities such as the Breton historian Arthur Le Moyne de La Borderie (who died in 1907). A historic song This confirms the historical character of this song: a tragic quarrel between husband and wife from two different branches of the noble family of Rohan. The remark that some Rohans were unpopular perhaps echoes the saying quoted in connection with the Siege of Guingamp song: "Debriñ en nev evel ma ra Roc'han" (He eats at the trough like a Rohan = he lives as a parasite) or the phrase "mab Roc'han" (son of Rohan) applied to a pig, according to a remark recorded in Gaidoz' "Revue Celtique" T. III, p.209 (1876-1878). |

An Itron Roc'han, Carnet N°2, p. 285 - 285 bis

|

p. 285 (Reun Ristual, 28 aout 1882) 1. Keit a oa bev Itron Roc'han, O Lonlonla, jamais je n'irai Kouske ar c'houer e-tal e dan, O Au bal du Plessis Guéméné 2. An aotrou zo aet da Bariz, Hag eñ distroet war e giz. 3. Pa oa deut an aotrou en-dro, Kresket ar c'hargoù war ar vro. 4. Hag an itron a lavare : - Aotrou n'eo ket mat, kement-se. 5. - Kement-se ne zell ket ouzhoc'h, Itron, m'ho ped, roit din ar peoc'h! - 6. 'N itron e savas droug enni: - Gwasket ma zud ne rafec'h mui. 7. Hag hi da lemel he gle(z)on Ha d'hen plantañ barzh e galon. 8. Keit a oa bev itron Roc'han Kouske ar c'houer e-tal e dan,.. . ( Kanet gant Jakez Kollober e Redene, pa oa Ristual en e ugent vloaz, ha Kollober en e driwec'h ha pevar-ugent, un den kozh-kozh, ha gwenn-kann.) _______ (Frettoù aour an Dukez Ana ) La Borderie pense qu'il s'agit de quelque démélé entre une Rohan-Rohan, et un Rohan-Chabot impopulaire comme frères [incert.] cf la chanson française: "lonlonla, jamais je n'irai Au bal du Plessis Guéméné" KLT gant Christian Souchon (c) 2021 |

p. 285 (Ronan Ristual, 28 aout 1882) 1. Du temps de Dame de Rohan, O Lonlonla, jamais je n'irai Dormait au chaud le paysan O Au bal du Plessis-Guéméné 2. Mais Monsieur s'en fut à Paris, Puis rentra dans son pays. 3. Et l'on a vu dès son retour, Les charges grimper tous les jours. 4. C'est alors que la Dame a dit: - Sire, on n'agit point ainsi. 5. - Cela ne vous regarde pas, Fichez-moi la paix avec ça! - 6. Elle alors bondit en disanti: - Vous n'opprimerez plus mes gens! - 7. Sa dague elle lui prend sans peur Pour la lui planter en plein coeur. 8. Du temps de Dame de Rohan Dormait au chaud le paysan,.. . ( Chanté par Jacques Collober à Rédéné, quand Ristual avait 20 ans, et Collober en avait 98, un vénérable vieillard à la blanche chevelure). _______ (Les ferrets d'or de la Duchesse Anne ) La Borderie pense qu'il s'agit de quelque démélé entre une Rohan-Rohan, et un Rohan-Chabot impopulaire comme tous ses frères cf. la chanson française: "Et lonlala Jamais je n'irai Au bal du Plessis-Guéméné" Traduction Christian Souchon (c) 2021 |

p. 285 (Ronan Ristual, August 28, 1882) 1. In the time of Lady Rohan, O Lonlonla, I will never go Farmers' hearths at night were kept warm O To the Plessis Guéméné ball 2. But Lord Rohan went to Paris, Then he returned to his countries. 3. The Lord had come back, From that day Taxes increased every way. 4. Once the Lady was heard to say: - Lord, What you do is no fair play. 5. - None of your business! You'd better Leave me alone with this matter! - 6. She said in a fit of anger: - You'll oppress my folks no longer! - 7. She drew from its sheath his dagger Stabbed him to death, made him stagger. 8. In the time of Lady Rohan Farmers' hearths at night were kept warm. (Sung by Jacques Collober in Rédéné, when Ristual was 20 and Collober was 98, a venerable old man with white hair). _______ (The Duchess Anne's gold studs) La Borderie thinks that this song relates some quarrel between a Lady Rohan-Rohan, and a Lord Rohan-Chabot who was unpopular like most of his kith and kin cf. French song: "And lonlala I'll never go To the Plessis-Guéméné ball " |

Les Dragons de Noailles (Lon lon la, let them go free)