Versions piémontaises et vénitiennes du "Roi Renaud"

Piedmontese and Venetian versions of "King Renaud"

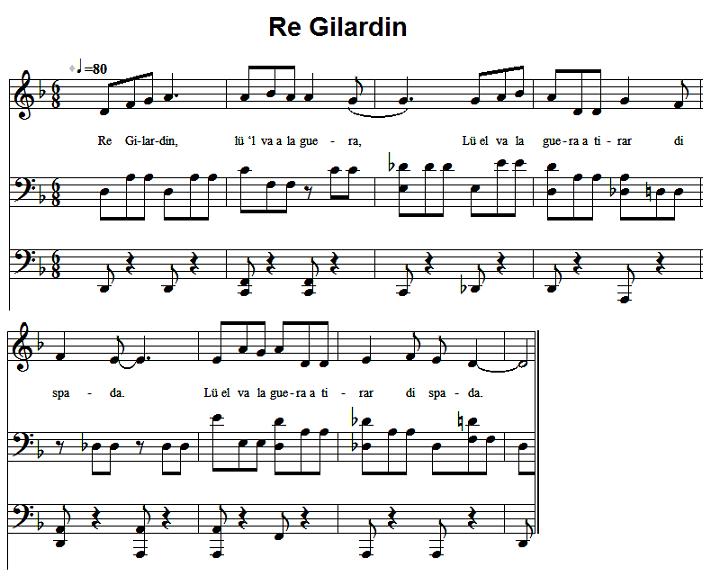

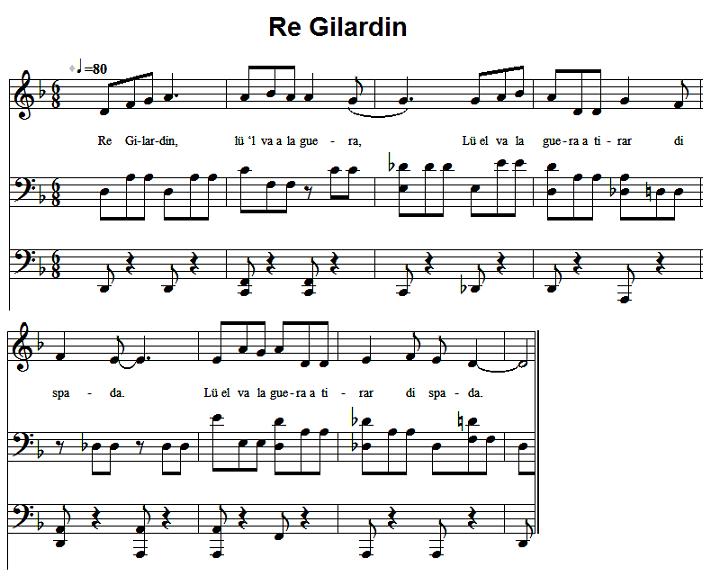

Mélodie

Arrangement par Christian Souchon (c) 2014

de la mélodie chantée par le groupe "La Ciapa Rusa"

1° MAL FERITO

La blessure mortelle * The deadly wound

| PIEMONTESE

| FRANCAIS

| ENGLISH

|

CANZONE PIEMONTESE

MAL FERITO

1. O s'a i sun tre giügadur

ch'a n'in giögo de le carte.

L'àn giögà e stragiögà,

e poi si taco a parole;

2. E da parole a cutei,

e da cutei a pistole.

Ël prim culp che lur l'àn fàit,

l'àn ferì lo ruè dla Spagna.

3. Gentil galand munta a caval,

për andar a la sua caza.

Sua mama a'l l'à vist rivar,

cun ün' ària cozì pàzia.

4. — O maman, pruntè-me ün let,

ün let di piüma d'oca;

E i ninsolin di téila d'lin,

e la querta di verdüra.

5. A mezanóit che mi sun mort

e'l me cavalin ant l'alba.

Süplì-me a l'autar magiur,

e'l me cavalin an piassa.

6. O crübì-me d'roze e fiur

e'l me cavalin d' giolifrada.

7. Tüta la gent ch'a passeran,

a diran: — Che gran dalmagi!

Che dalmagi dël cavalin

e ancur pi dio ruè dla Spagna! —

(Sale-Castelnuovo, Ganavese.

Dettata da Teresa Croce).

N°22, P. 149 di "Canti popolari del

Piemonte" publ. da Costantino Nigra (1888)

|

CANSON CATALAN

EL GUERRERO MAL HERIDO

[...]

[...]

1. Don Peyre s' ha mort al camp,

| Don Joan ve de batalla,

Sa mare l' en veu vení

| per un camp que verdejava:

6. - Mare 'neum'en á fé 'l llit,

| allá hont solía jaure.

No me 'l fasseu gayre be

| que no-hi dormiré pas gayre,

7. Moriré á la mija nit,

| mon xivall á punta d' alba.

A n-á mi m'enterrareu

| á l'alta de Santiague,

8. El xivall l'enterrareu

| á la porta dels esclaustres [...]

9. La gent que irán y vinran:

| «¿de qui son aquestas armas?»

Y vos mare responreu:

| «Del meu fill mort en batalla.»

"Romancerillo", N° 210, p. 171

|

CHANSON PIEMONTAISE

LA BLESSURE GRAVE

1. Oh, ce sont trois joueurs

Qui jouent aux cartes.

Ils ont joué et joué encore,

et puis se sont affrontés en paroles;

2. Après les paroles, les couteaux,

après les couteaux les pistolets.

La première balle qui fut tirée,

A blessé le roi d'Espagne.

3. Le vaillant noble monte à cheval,

pour aller à sa maison.

Sa mère l'a vu venir

Avec la mine déconfite...

4. — O mère, apprête-moi un lit,

un lit de plumes d'oie;

avec les linceuls de toile de lin,

et la couverture de tissu vert (?).

5. Car à minuit je serai mort

et mon cheval avant l'aube.

Ensevelis-moi au grand autel,

et mon cheval sur la place.

6. Couvre-moi de roses et de fleurs

et mon cheval d'œillets.

7. Et tous ceux qui passeront,

diront: "C'est grand dommage!

Grand dommage pour le cheval

plus encor pour le roi d'Espagne!"

(Sale-Castelnuovo, Ganavese.

Dettata da Teresa Croce).

N°22, P. 149 di "Canti popolari del

Piemonte" publ. da Costantino Nigra (1888)

|

CHANSON CATALANE

LE GUERRIER BLESSE

[...]

[...]

1. Don Pedro est mort à la guerre,

| Don Juan est revenu de la bataille,

Sa mère l'a vu venir

| par un champ qui verdissait:

6. - Mère, va-t-en me faire le lit,

| là où j'avais coutume de m'étendre.

Ne me le fais pas trop bien

| car je n'y dormirai guère,

7. Je mourrai à (la) minuit,

| mon cheval, lorsque poindra l'aube.

Alors, que l'on m'enterre

| sous le grand-autel de Saint-Jacques,

8. (Quant au) cheval, qu'on l'enterre

| á la porte des cloîtres [...]

9. Les gens qui iront et viendront:

| «De qui sont-ce là les armes?»

Et vous, mère, vous répondrez:

| «De mon fils, mort à la bataille.»

"Romancerillo", N° 210, p. 171, publié par Milà y Fontanas en 1882.

|

PIEDMONTESE SONG

DEADLY WOUND

1. There were three players

Three card players.

They played, they played their fill,

Then they started a joust of words;

2. Short of words, drew their knives,

after their knives, their pistols.

The first bullet that was shot,

Hit the king of Spain.

3. The gallant knight got on horse,

and returned home.

His mother saw him come

and he looked crestfallen...

4. — Mother, prepare a bed for me,

With a goose down filled mattress,

bed sheets of line cloth

and a blanket of green fabric (?).

5. For at midnight I'll have passed

and my horse tomorrow at dawn.

Bury me under the high altar,

and my horse in front of church.

6. Strew my tomb with rose petals

and my horse's with carnations.

7. And all passers-by,

will say: "What a pity!

Woe's me for the horse!

Still more for the King of Spain!"

(Sale-Castelnuovo, Ganavese.

Dettata da Teresa Croce).

N°22, P. 149 di "Canti popolari del

Piemonte" publ. da Costantino Nigra (1888)

|

CATALAN SONG

THE WOUNDED WARRIOR

[...]

[...]

1. Don Peyre was killed in action,

| Don Juan returned from battle,

His mother saw him come

| through a field turning green:

6. - Mother make me my bed,

| where I was used to lie.

But don't make it too snug

| since I shan't sleep for long,

7. I'll die at midnight,

| and my horse at dawning morn.

Let them bury me

| Underneath Saint James's altar.

8. My horse be buried

| at the gate of the cloisters [...]

9. Let people who come and go

| ask «Whose coat of arms is this?»

You, mother, shall answer:

| «My son's, who died at war.»

"Romancerillo", N° 210, p. 171, published by Manuel Milà y Fontanas in 1882.

|

Notes:

Commentaires de Costantino Nigra:

"[Dans "Mal ferito"], le fils qui rentre chez lui à cheval, blessé à mort, et qui dit à sa mère de lui préparer son lit, ne peut pas ne pas évoquer la chanson piémontaise de la "Morte occulta" (qui fait pendant à la ballade française du "Roi Renaud"). C'est ainsi que l"ària pàzia" (mine déconfite) du couplet 3 fait écho dans cette dernière à "Renaud, qui revient triste et chagrin". Ces analogies entre les deux chants m'avaient suggéré de publier la présente version, dans le N° XI de "Romania", regroupée avec les versions piémontaises de "Renaud". Je les reproduis ici aujourd'hui ensemble, mais sous 2 chapitres différents ["Mal ferito" et "Morte occulta"], car, après tout, rien ne prouve qu'elles aient la même origine.

La présente version, bien que moins obscure que celles d'Emilie publiées par Giuseppe Ferraro, "La lavandière" et "Le chevalier à la belle épée", n'en est pas pour autant absolument limpide.

Pas plus que le sont les trois chansons catalanes publiées par Francesc Pelai-Briz et qui correspondent strictement aux italiennes."

Remarques complémentaires

George Doncieux dans son "Romancero populaire de la France" (page 103, 1904) classe ce chant du Piémont au chapitre "Chanson catalane" au motif qu'il serait (ainsi qu'un chant gascon collecté à Massat en Ariège et publié par Pasquier, d'après Ruffié, en 1889) d'"importation catalane".

A titre d'illustration, on a mis ici en regard du "Mal Ferito" piémontais, un "Guerrero mal herido" catalan tiré du recueil de M. Milà y Fontanals.

. o O o .

On sait que la Sardaigne a été annexée par le royaume d'Aragon en 1323 qui y a établi un peuplement de Catalans jusqu'à la cession de l'île par l'Espagne en 1720. Quand la Maison de Savoie a pris possession de l'île, le catalan a cessé d'être une langue officielle. Il ne reste plus qu'un îlot linguistique: la ville d'Alghero où le catalan est parlé par 30.000 personnes.

Toutefois il n'apparaît pas que le chant piémontais soit plus proche du catalan que des versions françaises (d'oïl ou franco-provençales) du "Roi Renaud". On remarque combien le piémontais et le français sont apparentés, ce qui a certainement facilité la migration du chant de France vers l'Italie.

|

Comment by C. Nigra:

"[In "Mal ferito"], the son who, riding home deadly wounded, requests his mother to make his bed won't fail to remind us of the below Piedmontese song of the concealed death, "Morte occulta", (the counterpart to the French ballad of "King Renaud"). For instance the "ària pàzia" (crestfallen look) in stanza 3 is a reminiscence of the sentence "Renaud comes home sad and downcast". These analogies between both songs had prompted me to append the present version, in the release Nr XI of the journal "Romania", to a series of Piedmontese versions of "Renaud". In the present book I print both songs in two different chapters [ titled "Mal ferito" and "Morte occulta"], since there is no definite evidence that they do have the same origin.

The version at hand, though less obscure than those of Emily published by Giuseppe Ferraro under the titles "The washerwoman" and "The knight with the beautiful sword", is nonetheless partly incomprehensible.

So are the three Catalan songs published by Francesc Pelai-Briz that best correspond with Italian counterparts."

Additional remarks

George Doncieux, in his "Romancero populaire de la France" (page 103, 1904) quotes this Piedmontese song in a chapter dedicated to "Catalan songs" because it was allegedly "imported from Catalonia" (as was, so writes its collector Ruffié, a Gascon song noted at Massat in the département Ariège and published by Pasquier in 1889).

In support of this claim, the Piedmontese "Mal Ferito" and the Catalan "Guerrero mal herido", from M. Milà y Fontanals' collection are displayed side by side.

. o O o .

It will be remembered that Sardinia was annexed by the Kingdom of Aragon in 1323 and that Catalans settled on the island until it was given up by Spain in 1720. When the House of Savoy came to rule on Sardinia, Catalan ceased to be an official language and there is but a small linguistic island left, to wit the city of Alghero where it is spoken by less than 30.000 people.

However it does not appear that the Piedmontese song be any nearer to the Catalan ballad than are the French versions (in the language of Oil and Francoprovencal) of "King Renaud". Since the Piedmontese and the French languages are rather similar, the wandering of the song from France to Italy was an easy thing.

|

2° LA MORTE OCCULTA

La mort cachée * The concealed death

| PIEMONTESE

| FRANCAIS

| ENGLISH

|

A. MORTE OCCULTA

1. — O venì vëde, ël me car fì,

ch'la vostra fema a la fàit ün fì.

2. - Mi vöi pa vëde el me car fì,

che nóster sgnur mi ciama mi.

3. Andè-me fè fè ün letin bianc,

che mi srai mort al matin duman.

4 Andè-m-lo fé fé ant l'ascondü,

che la mia fema a lo sàpia nen. —

5. Quand a na ven la matinà,

i servitur s'büto a piurà.

6. — Dizi-me 'n po', mia mare grand,

che i servitur a piuro tant?

7. — I cavai a sun andàit brüvé,

i dui pi bei l'an lassa niè.

8. — Dizì-e 'n po', mia mare grand,

për dui cavai ch'a piuro nen tant.

9. Che da 'n pajola che 'm leverò,

d'àutri pi bei na cumprerò.

10. - Dizì-me 'n po', mia mare grand,

perchè le serve na piuro tant?

11. — L'è la lessia sun andàite lavè,

i pi bei mantij l'àn lassa niè.

12. — Dizi-e 'n po', mia mare grand,

per i mantij eh 'a piuro nen tant.

13. Che da 'n pajola che 'm leverò,

d'àutri pi bei ne cumprerò.

14. Dizi-me 'n po', mia mare grand,

perchè le cioche a suno tant?

15. — J'è mort ël fiöl d'un gran signur,

e le cioche a i fan so onur.

16 — Dizi-me 'n po', mia mare grand,

che i vostri öi a na piuro tant?

17. — Ant la cüzina na sun andà,

a l'è lo füm ch'a 'm fa piurà.

18 — Dizi-me 'n po', mia mare grand,

perchè i préive na canto tant?

19. — S'a l'è i préive na canto

tant la grossa festa ch'a fan duman.

20 — Mi da 'n pajola che 'm leverò,

la vesta russa mi meterò.

21. — Vui di néir e mi di gris,

andruma a la moda dël païs.

22 - Dizi-me 'n po', mia mare grand,

j'è d'terra frësca sut al nost banc.

23. — Nora mia, mi pöss pa pi scüzè,

vost mari l'è mort e suterè. —

(Villa Castelnuovo e Sale-Castelnuovo,

Canavese. Cantata da Domenica Bracco)

|

A. LA MORT CACHEE

1. — O venez donc voir, mon cher fils,

Votre épouse a mis au monde un fils.

2. - Je ne veux pas voir mon cher fils:

Le Seigneur me rappelle à lui.

3. Allez me faire un lit tout blanc:

Je serai mort demain matin.

4. Faites-le moi faire en cachette,

que ma femme n'en sache rien. —

5. Lorsque le matin arriva,

les serviteurs se mirent à pleurer.

6. — Dites-moi un peu, belle-mère,

Qu'ont les serviteurs à tant pleurer?

7. — Des chevaux qu'on à menés boire,

Les deux plus beaux ses sont noyés.

8. — Dites-leur un peu, belle-mère,

Qu'il ne leur faut point tant pleurer.

9. Quand je me relèverai de couches,

d'autres plus beaux j'achèterai.

10. - Dites-moi un peu, belle-mère,

pourquoi les servantes pleurent tant?

11. — Au lavoir elles sont allées,

Les plus beaux draps furent emportés.

12. — Dites-leur un peu, belle-mère,

pour des draps de ne pleurer tant.

13. Quand je me relèverai de couches,

d'autres plus beaux j'achèterai.

14. - Dites-moi un peu, belle-mère,

pourquoi les cloches sonnent tant?

15. — Est mort le fils d'un grand seigneur,

et les cloches lui font honneur.

16 — Dites-moi un peu, belle-mère,

Qu'ont donc vos yeux à pleurer tant?

17. — Devant la cuisine je suis passée,

et c'est la fumée qui me fait pleurer.

18 — Dites-moi un peu, belle-mère,

pourquoi les prêtres chantent tant?

19. — Si les prêtres chantent tant

C'est pour la grande fête de demain.

20 — Quand je me relèverai de couches,

Je mettrai mes vêtements rouges.

21. — Vous du noir et moi du gris:

Nous suivrons la mode du pays.

22 - Dites-moi un peu belle mère,

La terre est fraîche sous notre banc.

23. — Belle-fille, je ne peux plus le cacher

votre mari est mort et enterré. —

(Villa Castelnuovo à Sale-Castelnuovo,

Canavese. Chanté par Domenica Bracco)

|

A. DEATH CONCEALED

1. — O come and see, my dear son!

Your wife gave birth to a son.

2. - I don't want to see my dear son.

The Lord has called me home.

3. Go and have a white bed made for me

who will be dead tomorrow morning.

4. But be it made unknown to all,

so that my wife does not hear of it! —

5. When the morning came,

the servants started weeping.

6. — Just a word, mother-in-law:

Why do the servants cry so much?

7. — While they were watering the horses,

they've let the finest two drown.

8. — Just tell them, mother-in-law,

not to cry as much about two horses!

9. When I recover from childbirth,

I'll buy two new still finer horses.

10. - Just a word, mother-in-law:

Why do the maids weep so much?

11. — While washing our coats,

they have let go the finest ones.

12. — Just tell them, mother-in-law,

not to cry so much about these coats!

13. When from this childbed I rise,

I shall buy new finer coats.

14. - Just tell me, mother-in-law:

why do the bells toll so loudly?

15. — The son of a great lord is dead,

and the bells toll in his honour.

16 — Just tell me, mother-in-law:

Why do your eyes weep as much?

17. — As I walked past the kitchen

the smoke made my eyes weep.

18 — Just tell me, mother-in-law:

Why do the priests sing so much?

19. — these priests will sing at the great

feast that takes place tomorrow.

20 — When I rise from childbed,

I shall put on my red dress.

21. — You'll go in black, I in grey:

We'll dress as local custom requires.

22 - Just tell me, mother-in-law, why

did they dig the earth near our bench?

23. — Daughter, I can conceal it no more:

Your husband is dead and buried.

(Villa Castelnuovo near Sale-Castelnuovo,

Canavese. Sung by Domenica Bracco)

|

Notes:

Commentaire :

Dans l'ouvrage de C. Nigra, ce chant, repéré A, est suivi de 6 variantes:

B. "Coza vol dir, maman, che le cioche n'an sunho tant?" ("Qu'est-ce que cela veut dire, maman, que les cloches sonnent tant). Autres questions sur les menuisiers ("mesdabosc") censés confectionner un berceau ("cünha"), les servantes ("creade") et les laquais ("lachè") qui pleurent les vêtements qu'elles ont laissé échapper et le carrosse qui s'est brisé; enfin sur la terre fraîche qui amène la réponse: "ch'à j'é mort signur lo re" ("parce qu'est mort sire le roi"). Chanté par une bonne de Turin, originaire d'Albe.

C. "Pruntè-me ün let, la mamin grand" ("Prépare-moi un lit, ma chère mère). Suivent les questions de la bru auxquelles la belle-mère commence toujours par répondre: "S'a piuro/ciapülo, lassè-je piurè/ciapulè..." (S'ils pleurent, clouent, laisse les pleurer/clouer...) jusqu'à la remise des clés: "Pié la ciaf dël me castel, che vöi andè-me sutrè con chiel" ("Prenez la clef de mon château: je veux être enterré avec lui.") Dicté par une paysanne de Collina di Torino.

D. "Ven da la guera lo re Lüis, ven da la guera tüto feri." ("Le roi Louis revient de guerre, revient de guerre couvert de blessures."). Commence aussitôt le jeu des questions et réponses: les cloches qui sonnent pour le nouvel an, les servantes et les chemises brûlées, les cochers ("carossé") et les chevaux noyés, les menuisiers et le berceau. Vient ensuite la question de la robe à mettre, du lieu où seront célébrées les relevailles, chez les Capucins qui sont très matinaux. Enfin la terre sous le banc oblige la belle-mère à avouer que "lo re Lüis è mort e suterè". Sa bru lui remet les clés du jardin et du château car elle veut aller retrouver son bel amour: "Vöi andè truvè me bel corin". (Turin: dicté à G. Flechia par G. Morra-Fassetti)

E. "Ven da la casa lo re Rinald, ven da la cassa, l'e tüt feri". (Le roi Renaud revient de chasse, revient de chasse bien blessé). Ici aussi les questions de la bru suivent immédiatement: les chevaux qui se noient, les chemises qui qu'on a laissé brûler ("àn lassà brüzè"), les cloches qui sonnent en l'honneur de la mort d'un grand seigneur, les menuisiers qui confectionnent des berceaux. Puis la question de larobe à mettre.

Ici se place l'épisode des trois enfants qui désignent "la dama d'cul gran signur ch'a l'àn sepll-'lo l'àutër giurn" (la dame de ce grand seigneur que l'on a enseveli l'autre jour), mais bien-sûr "parlo da pcit" (ils disent des bêtises). La terre fraîche provoque l'aveu.

Quand sa belle mère lui dit: "Mi i'l l'ài piurà, ch'a l'era me fi, piurè-lo vui, ch'a l'era vost mari!" (moi je l'ai pleuré, car c'était mon fils, pleurez-le, vous, car c'était votre mari), la bru répond: "Se i mort a parléisso ai vif, parleria na volta al me car Lüis. Se i vif a parléisso ai mort, parleria na volta al me car cunsort". (Si les morts parlaient aux vivants, à mon tour je parlerais à mon cher Louis. Si les vivants parlaient aux morts, à mon tour je parlerais à mon cher époux). (Bene- Vagienna près de Mondovi. Transmis par P. Fenoglio)

F. "Ven da la guera re Rinaldo, ven da la guera, l'è tüt feri". (Le roi Renaud revient de guerre, revient de guerre bien blessé); Se limite aux questions sur les cloches, les menuisiers, le lavandières, les cochers, la robe rouge et la terre fraîche, pour conclure "Cara norëta, pöss pa pi scuzè, che'l re Rinaldo è nmort e suterè". (Ma chère bru, je ne peux plus te le cacher, le roi Renaud est mort et enterré).

G. "Ven da la guera ël re Carlin, ven da la guera tüto feri." Les questions habituelles relatives aux cloches, aux menuisiers, aux cochers, aux chemises qui suivent sans transition cette introduction, appellent toutes la remarque de la jeune femme que "Che 'l re Carlin a venirà...", quand le roi Carlin reviendra, il remplacera l'objet perdu par un autre bien plus beau. La question sur la robe à mettre entraîne ici la réponse "Vui di néir e mi di gris, cum'a j'é la moda a Paris!" (Vous en noir et moi en gris, comme c'est la mode à Paris!) (Informatrice originaire d'Altare près de Savone et habitant Turin).

On pourrait croire que cette longue liste de "Rois Renaud" piémontais s'arrête-là. Il n'en est rien: le chant ci-après trouvé sur un site Internet (qui le rapproche abusivement du chant écossais "Clerk Colvill") donne, en prime, la mélodie qui manque dans l'ouvrage de Nigra. Le dialecte de la région d'Alexandrie apparaît ici plus proche de l'italien "officiel" que dans les chants précédents.

|

Les dialectes piémontais

(Dom=Domodossola, Versaj=Vercelli, Lissandria=Alexandrie, Pinareul=Pignerol, Aut/Bass Monfra=Haut/Bas Montferrat)

Selon Wikipedia, parlé par 2 M d'individus

et compris en outre par 1 M de personnes.

Mais où donc parle-t-on italien?

|

comment:

In C. Nigra's collection, this song, tagged as A, is followed by 6 variants:

B. "Coza vol dir, maman, che le cioche n'an sunho tant?" ("What does it mean, mother, that the bells ring so loud). The girl asks questions about the carpenters ("mesdabosc") allegedly making a cradle ("cünha"), the weeping maidservants ("creade") and menservants ("lachè"), the clothes that were let go in the stream and the carriage that was damaged; last about the turned over earth with the answer: "ch'à j'é mort signur lo re" ("because the Lord King is dead"). Sung by par Turin maid, who was born in Alba.

C. "Pruntè-me ün let, la mamin grand" ("Make me a bed, my dear mother). Followed by questions asked by the girl which her mother-in-law at first repeatedly answers: "S'a piuro/ciapülo, lassè-je piurè/ciapulè..." (If they cry, nail..., let them cry/nail...) until the girl asks for her keys: "Pié la ciaf dël me castel, che vöi andè-me sutrè con chiel" ("Take the key of my manor: I will be buried with him.") Dictated by a Collina di Torino country woman.

D. "Ven da la guera lo re Lüis, ven da la guera tüto feri." ("King Lewis returns from war, returns from war and his body is covered with wounds."). Here starts the usual cruel game of questions and answers: the bells ringing to celebrate New Yearl, the maids and the burnt shirts, the coachmen ("carossé") who let the horses drown, the joiners and the cradle. Then comes the question about which dress to put on, the best place for the churching which will be the church of the Capuchin monks, but she will have to get up early in the morning. At last the question about the freshly dug earth underneath the bench forces the mother-in-law to admit that "lo re Lüis è mort e suterè" (King Lewis is dead and buried). The girl hands her out the keys of yard and manor, as she wants to join her fair love in death: "Vöi andè truvè me bel corin". (Turin: dictated to G. Flechia by G. Morra-Fassetti)

E. "Ven da la casa lo re Rinald, ven da la cassa, l'e tüt feri". (King Renaud comes home from hunting deriously injured). Here too this statement is abruptly followed by the girl's questions: the drowned horses, the shirts that were singed ("àn lassà brüzè"), the bells tolling to honour a deceded great lord, the joiners who make cradles. The the right dress to put on problem.

Now comes a new episode: three children point to "la dama d'cul gran signur ch'a l'àn sepll-'lo l'àutër giurn" (the wife of the great lord whom they buried recently), but of course "parlo da pcit" (they talk nonsense). The earth recently turned over causes the mother-in-law to admit the death.

When the latter says: "Mi i'l l'ài piurà, ch'a l'era me fi, piurè-lo vui, ch'a l'era vost mari!" (I mourned for him who was my son, you'll mourn for him who was your husband), the girl answers: "Se i mort a parléisso ai vif, parleria na volta al me car Lüis. Se i vif a parléisso ai mort, parleria na volta al me car cunsort". (If the dead did speak to the living, on my turn I would speak to my dear Lewis. If the living did speak to the dead, on my turn I would speak to my dear husband). (Bene- Vagienna near Mondovi. Sent in by P. Fenoglio)

F. "Ven da la guera re Rinaldo, ven da la guera, l'è tüt feri". (King Renaud returns from war, returns from war seriously wounded); only questions about the bells, the joiners, the washerwomen, the coaches, the red dress and the fresh earth are mentioned in this song that ends up with "Cara norëta, pöss pa pi scuzè, che'l re Rinaldo è nmort e suterè". (My dear daughter-in-law, I can't conceal it any more: King Renaud is dead and buried).

G. "Ven da la guera ël re Carlin, ven da la guera tüto feri." The well-known questions about the bells, the joiners, the carriage drivers, the damaged clothes, coming after this introduction, without any transition, are all followed by the girl's remark: "Che 'l re Carlin a venirà...", when King Carlin returns, he will replace the item lost with a far better one. The question how to dress is answered as follows: "Vui di néir e mi di gris, cum'a j'é la moda a Paris!" (You in black an I in grey, it's the new fashion in Paris!) (Learnt from the singing of an Altare woman (near Savona) who lived in Turin).

One might think that this long series of Piedmontese "Kings Renaud" comes here to an end. Not at all: the next song that was found on an Internet site (that wrongly parallels it with the Scots ballad "Clerk Colvill") gives, in addition, the tune missing in Nigra's collection. The dialect used in the Alexandria area seems nearer to "normal" Italian than in the foregoing songs.

|

3° RE GILARDIN

Le roi Gillardin * King Gilardin

(Source: http://www.nspeak.com/allende/comenius/bamepec/re_gilardin_clerk_colvill.htm)

1. Re Gilardin, lü ‘l va a la guera,

Lü el va la guera a tirar di spada. (bis)

2. O quand ‘l’è stai mità la strada,

Re Gilardin ‘l’è restai ferito.

3. Re Gilardin ritorna indietro,

Dalla sua mamma vò ‘ndà a morire.

4. O tun tun tun pica a la porta.

“O mamma mia che mi son morto.”

5. “O pica pian caro ‘l mio figlio,

Che la to dona ‘l g’à ‘n picul fante.”

6. “O madona la mia madona

Cosa vol dire ch’i cantan tanto?”

7. “O nuretta, la mia nuretta,

I g’fan ‘legria ai soldati.”

8. “O madonna, la mia madona,

Disem che moda ho da vestirmi?”

9. “Vestiti di rosso, vestiti di nero,

Che le brunette stanno più bene.”

10. O quand l’è stai ‘nt l üs de la chiesa,

D’un cirighello si l’à incontrato:

“Bundì bongiur an vui vedovella.”

11. “O no no no che non son vedovella,

‘g o ‘l fante in cüna e ‘l marito in guera.”

12. “O si si si che voi sei vedovella,

Vostro marì l’è tri dì che ‘l fa terra.”

13. “O tera o tera apriti ‘n quatro,

Volio vedere il mio cuor reale.”

14. “La tua boca la sa di rose,

‘nvece la mia la sa di terra.”

|

1. Le roi Gillardin s'en va-t-en guerre,

S'en va-t-en guerre jouer de l'épée. (bis)

2. Et au beau milieu de la rue,

Le roi Gillardin demeura blessé.

3. Le roi Gillardin s'en retourne,

Chez sa mère: c'est là qu'il va mourir.

4. Et "boum, boum", il frappe à la porte.

“Mère ouvrez-moi: je vais mourir!”

5. “Frappe moins fort mon fils chéri,

Car ta femme a accouché d'un petit enfant.”

6. “O Madame ma belle-mère,

Que signifient tous ces chants?”

7. “Ma petite bru, tous ces chants

C'est pour amuser les soldats.”

8. “O Madame ma belle-mère,

Dites-moi comment me vêtir?”

9. “Vêts-toi de rouge, vêts-toi de noir,

C'est ce qui sied le mieux aux brunes.”

10. Et quand elle arriva à la porte de l'église,

Elle rencontra un enfant de chœur:

“Bonjour, bonjour à vous, la veuve!”

11. “Mais non, voyons, je ne suis pas veuve,

J'ai un enfant au berceau et mon mari à la guerre.”

12. “Oh, que si! Vous êtes veuve!

Cela fait trois jours que votre mari on l'a fait enterrer.”

13. “O terre, O terre, ouvre-toi en quatre!,

Je veux te voir, roi de mon cœur”

14. “Ta bouche a la saveur des roses,

Mais la mienne a le goût de terre.”

|

1. King Gilardin was in the war,

Was in the war wielding his word. (bis)

2. When he was in the middle in the street,

King Gilardin was wounded.

3. King Gilardin goes back home,

At his mother's house he wanted to die.

4. Bang, bang! He thumped at the door.

“O Mother, I am near to die.”

5. “Don't thump so hard, my son,

Your wife has just given birth to a boy.”

6. “My Lady my mother-in-law

What does all their singing mean?”

7. “O my daughter-in-law,

They want to entertain the soldiers.”

8. “My Lady my mother-in-law

Tell me, how shall I dress?”

9. “Dress in red or dress in white,

It fits brunettes perfectly .”

10. When she came to the church gate,

She encountered an altar boy:

“A wish you a good day, new widow.”

11. “By no means am I a new widow,

I've a child in its cradle and a husband at war.”

12. “O yes, you are a new widow,

Your husband was buried three days ago.”

13. “O earth, open up in four corners!

I want to see the king of my heart.”

14. “Your mouth has a taste of rose,

Whereas mine has a taste of earth.”

|

Notes:

Commentaire :

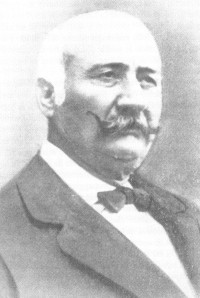

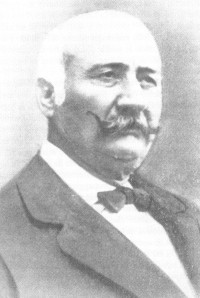

Le philologue italien Costantino Nigra (1828 - 1907) fait suivre ses sept équivalents piémontais du "Roi Renaud" d'un exposé qu'on peut résumer comme suit:

Svend Grundtvig dans son étude de 1881 intitulée "Elveskud: chants populaires danois...et bretons" concluait à l'origine celtique de la ballade d'Olaf et de l'elfe. Le médiéviste Gaston Paris (1839 - 1903) ( dans le n°41 de la revue "Romania" de janvier 1882, revue que ce chartiste avait créée en 1872) envisageait d'examiner comment ce chant s'était transmis à l'Europe entière. C. Nigra propose d'y contribuer grâce à "ses" chants piémontais" et l'invite à ne plus intituler cette ballade "Jean Renaud" (titre rare), mais "Renaud" tout court, ou à suivre son exemple et à l'appeler "La mort cachée", qui convient à toutes les versions.

Le premier auteur italien a avoir signalé l'existence de cette chanson fut Luigi Carrer dans un article paru à Venise en 1841. Ce n'est qu'en 1854 qu'on mentionna son existence dans le Piémont. Widter-Wolf, Giuseppe Ferraro, Ive, Mazzatinti et Salvatori publièrent des chansons analogues collectées en Vénétie, dans la région de Ferrare, en Emilie ("La lavandaia"), en Istrie, en Ombrie ("Ruggiero") et dans le Latium ("Luggieri"), dans des ouvrages publiés entre 1854 et 1879.

Nigra fit paraître les sept chants piémontais ci-dessus pour la première fois en 1882 dans le tome XI de la revue "Romania", accompagnés d'un conte qui se rattache auxdites chansons ainsi qu'à leurs versions scandinaves et bretonnes: "Il dono della fata" (Le présent de la fée):

"Un chasseur rencontre une fée dans la montagne, qui lui demande de l'épouser. Etant déjà marié, il refuse. La fée lui remet une cassette contenant un cadeau pour la jeune épouse, en lui recommandant de la lui remettre en main propre et de ne pas l'ouvrir. Bien entendu, chemin faisant il l'ouvre et y trouve une magnifique ceinture tissée d'or et d'argent. Pour juger de l'effet qu'elle fera sur son épouse, il en ceint le tronc d'un arbre. C'est alors que la ceinture prend feu et que l'arbre est foudroyé. Le chasseur, atteint par l'éclair se traîne jusqu'à sa maison, s'étend sur son lit et meurt."

|

Costantino Nigra (1828 - 1907)

|

Comment :

The Italian philologist Costantino Nigra (1828 - 1907) appends to his seven Piedmontese counterparts to "King Renaud" an essay that sums up as follows:

Svend Grundtvig in his 1881 survey titled "Elveskud: folk songs of Denmark...and Brittany" ascribed a Celtic origin to the ballad of Olaf and the elf. The medievalist Gaston Paris (1839 - 1903) (in the January 1882 copy #41 of the periodical "Romania", which he had founded 10years earlier) considered investigating how this ballad had spread throughout Europe. C. Nigra presentshis "Piedmontese songs " as his contribution to this work and questions the general title given by the scholar to the ballad, "Jean Renaud" (a seldom encountered title), that should be replaced by "Renaud" only, or as he does by "The concealed death", that suits all versions.

The first Italian author who pointed to Italian equivalents to that song was Luigi Carrer in his article published in Venice in 1841. It was not until 1854 that its presence in Piedmont was mentioned. Widter-Wolf, Giuseppe Ferraro, Ive, Mazzatinti and Salvatori published similar songs that they had gathered in Venetia, the Ferrara area, Emilia ("La lavandaia"), Istria, in Umbria ("Ruggiero") and the Latium ("Luggieri"), in collections printed between 1854 and 1879.

Nigra first published in 1882 the seven Piedmontese songs above in book XI of the review "Romania", along with a tale related to them, as well as to their Scandinavian and Breton equivalents: "Il dono della fata" (The fairy's present):

"A hunter encounters in the mountain a fairy who proposes to him. As he's already married, he refuses. The fairy gives him a casket containing a gift for the young wife, and advises him to hand it out only to her and by no means to open it. Of course, on his way home he cannot refrain from opening it and finds a splendid belt interwoven with gold and silver threads. Just to know what it will look like when worn by his wife, he ties it round the trunk of a tree. Suddenly the belt catches fire when the tree is hit by a flash of lightning. The hunter is hit, too and he hardly manages to drag himself home. He crumbles on his bed and dies."

|

4° IL RE CARLINO

Le roi Carlin * King Carlin

Collecté par Giuseppe Ferraro, "Canti popolari monferrini", N°26, p.34, 1870

1. Ra soi mamma ant u giardin

R'aspicciava lo re Carlin

- Alegr, alegr, o re Carlin,

Ra vostra dona r'ha fantulin.

2. - Mi an im'na poss rallegrèe tant,

Ch'an il vegrô nent a vnî grand:

Fèm'u lecc cun i lansoi di lin,

Che mi sarô mort a ra mattin; -

3. Su ni ven poi ra meza nocc

Candeire avische e u lim l'è smort.

4. - Cosa vôl dî, o mama granda,

Che li campan-nhe i sunnhu tant?

-Lasèi sunèe, lasèi sunèe,

Fan aligria ar fijô du re.

5. - Cosa vôl dî, o mama granda,

Che li vostr'occ i piansu tant?

- R'è ra fim di ra bigà,

Che li mei occ i sun csî bagnà.

6. - Cosa vôl dî, o mama granda,

J meistr da bosch i tambisso tant?

-Lassèi fèe, lasèi an po fè

I fan ra chin-nhe ar fijô du re.

7. - Cosa vôl dî, o mama granda,

Che i dumestich i piuru tant?

- I han amnà a beive i cavai du re,

E dui i han lasai nijè.

8. - A vi dig, o mamma granda,

Cma vistirumma nui duman?

— Mi di bianc e vui di gris,

Andrumma a l'isanza di nostr pais. —

9. — Che dona ch'r'è mai quella?

L'è in pcà ch'ra sia viduella. —

10. — A vi dig vui, mama granda,

Sentì csa ch'u dis ist pcit infant? —

— O lasèle, o noira, pira dì,

Andumma a ra messa ch'r'ha da fini.

11. — Cosa vól dì, o mama granda,

Ra tera fresca sutta ai banch?

— O povra mi nun mi poss pi schisèe:

Ir vostr Carlin l'è mort e suterèe. —

12. — O mama, dème ra ciav dir me castel

A vói andèe cun ir me curin bell. —

|

1. Quand sa mère allait au jardin

Elle aperçut le roi Carlin

- Réjouissez-vous donc, roi Carlin

Votre femme a un beau bambin.

2. - Moi je ne m'en peux réjouir tant,

Ne le verrai devenir grand:

Fais mon lit de linceuls de lin,

Car je serai mort de bon matin; -

3. Lorsque minuit survint alors

Des bougies brûlaient pour le mort.

4. - Mais pourquoi donc, O mère-grand (=belle-mère)

Les cloches sonnent-elles tant?

- Qu'elles sonnent, laisse-les donc,

Fêter le royal rejeton!

5. - Mais pourquoi donc, O mère-grand,

Vois-je vos yeux pleurer autant ?

- C'est la bujade (lessive) et sa fumée,

J'en ai les yeux tout embués .

6. - Mais pourquoi donc O mère-grand,

Les maîtres du bois clouent-ils tant?

- Oh, laisse-les clouer ma foi:

l

Pour le berceau du fils du roi.

7. - Mais pourquoi donc O mère-grand,

Les domestiques pleurent tant?

- Menant boire les chevaux du roi,

Voilà que deux d'entre eux se noient.

8. - Mère-grand, conseillez-moi bien:

Quels habits mettrons-nous demain?

— Moi des blancs, vous-même des gris,

C'est l'usage dans notre pays. —

9. — Qui est la dame que voilà?

Veuve depuis peu, n'est-ce pas . —

10. — Entendez-vous, ma mère-grand,

Ce qu'ont dit ces petits enfants? —

— Laissez-les, ma bru, dire pis,

La messe, allons, touche à sa fin.

11. — Mais pourquoi donc, O mère-grand,

La terre fraîche sous le banc?

— Je ne peux plus le déguiser:

Carlin est mort et enterré. —

12. — Mère la clé de mon château

Je rejoins mon amour (petit cœur) si beau. —

|

1. His mother went out to the garden

And spied her son, the king Carlin

- Cheer up, cheer up, o King Carlin,

Your wife gave birth to a small son.

2. - I cannot rejoice that much,

Since I'll never see him grow up:

Make me my bed with linen sheets,

For I shall be dead next morning; -

3. And really, when midnight came

Candles were lit near the dead king.

4. - What does it mean, grandmother dear (=mother-in-law),

Why do the bells ring so loud?

-Let them ring, dear, let them ring,

It's to make them cheer the king's son.

5. - What does it mean, grandmother dear,

That your eyes overflow with tears?

- They have been doing the washing,

And the smoke got into my eyes.

6. - What does it mean, grandmother dear,

Why do the carpenters nail so much?

-Let them nail, just let them nail

They make a cradle for your son.

7. - What does it mean, grandmother dear,

Why do our menservants weep so much?

- When they watered the king's horses,

The have let two of them drown.

8. - But tell me, grandmother dear,

What dresses shall we put on tomorrow?

— I my white dress, you your grey one,

We'll comply with local custom. —

9. — Did you ever see such a lady?

Dolls herself up though a widow. —

10. — O now tell me, grandmother dear,

Did you hear what this child has said? —

— Never mind, daughter, may they tell still worse,

Let's go to mass before it's over.

11. — What does it mean, grandmother dear,

This earth turned over near our bench?

— Poor child, can conceal it no more:

Your Carlin is dead and buried. —

12. — Mother give me the key to the castle

I will follow my precious jewel. —

|

.

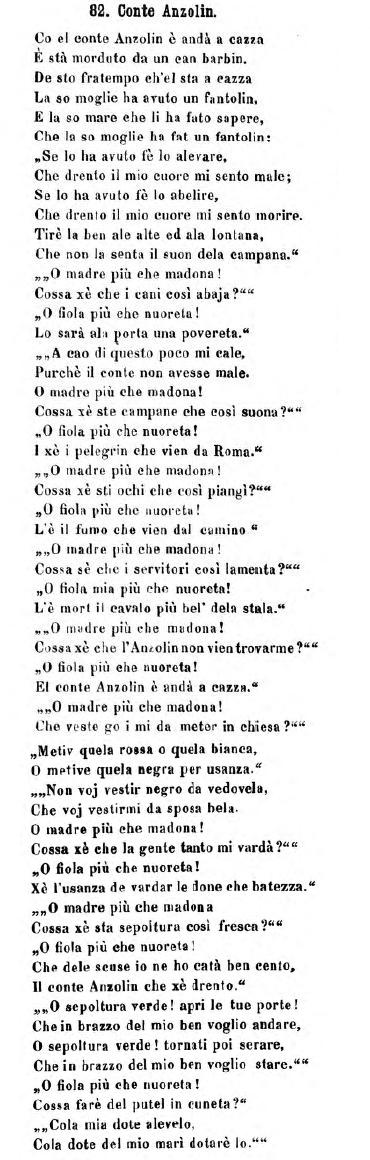

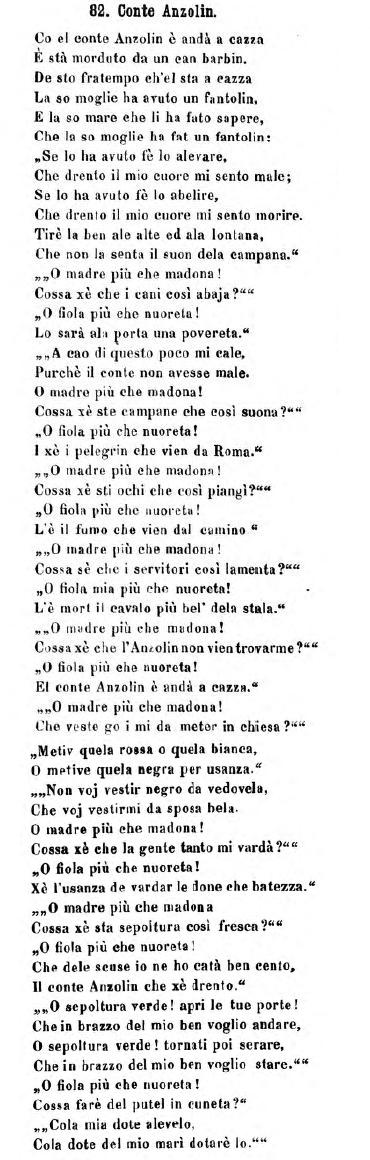

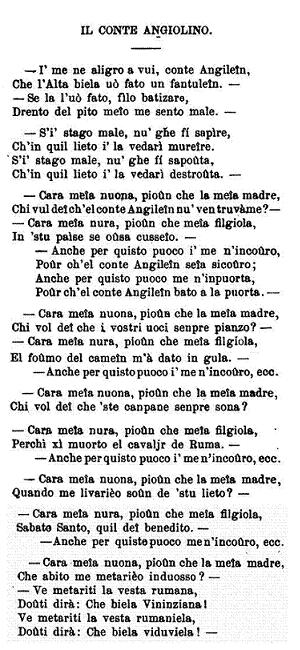

5° Il Conte Angiolino

La Canzone du Comte Anzolin * The Venetian song of Count Anzolin

Collectée par Luigi Carre, Adolf Wolf, G.Ferraro et Antonio Ive

Le recueil du Dr Giuseppe Ferraro (1845-1907) de l'Ecole Normale Supérieure de Pise, "Canti popolari Monferrini" (Turin-Florence, Loescher 1870), fait partie d'une collection qui, à l'initiative de D. Comparetti et A. d'Ancona, se proposait de publier les chants et contes populaires de toute l'Italie. Dans "Canti popolari", G. Ferraro s'en tient strictement à sa localité d'origine, Carpeneto, dans le Haut-Montferrat, Province d'Alexandrie.

On serait tenté de croire que le Piémont seul, parmi les provinces italiennes possédait des chants narratifs. Il n'en est rien:

Une "Canzone" vénitienne composée de quatrains en décasyllabes rimant deux par deux a été notée trois fois. Le résumé en prose publié par le Vénitien Luigi Carrer en 1838 dans "Prose e poesie", IV est même l'une des toutes premières notations du thème populaire de la "mort cachée".

Le chant du "Comte Azolin" est ensuite collecté à Vicence par Georg Widter et paraît en 1864 dans ses "Volkslieder aus Venetien".

Giuseppe Ferraro rencontre le même personnage dont le nom est déformé en "Cagnolino" à Pontelagoscuro, en Piémont dans la province de Ferrare.

Enfin Antonio Ive, dans ses "Canti popolari istriani" parus en 1877, présente à son tour un chant de Rovigno en Istrie (aujourd'hui Rovinj) contant la triste histoire du Conte Angiolino.

Aucune de ces publications ne comporte malheureusement de notation musicale!

L'histoire est sensiblement toujours la même:

Le comte Anzolin revient de la chasse. Il a été mordu par un chien. Sa mère lui apprend la naissance de son enfant. Il lui répond: "Fais-le baptiser! Moi, je vais mourir, mais que ma femme ne le sache pas...". Vient alors le jeu des questions et réponses entre "ma chère belle-mère qui m'est plus qu'une mère" et "ma chère belle-fille qui m'est plus q'une fille". Ici les cloches sonnnet pour un pèlerin de Rome, les relevailles ont lieu le jour de la saint-Marc ou le samedi saint...L'histoire se termine par l'imprécation de la jeune femme: "O tombeau, ouvre tes portes! Je veux aller dans les bras de mon amour!"

|

The collection composed by Dr Giuseppe Ferraro (1845-1907), who taught at the Pisa highschool for training of teachers, is titled "Canti popolari Monferrini" (Turin-Florence, Loescher 1870). It is part of a series of collections initiated by D. Comparetti and A. d'Ancona, whose purpose was to encompass all songs and folk tales of the whole of Italy. In "Canti popolari", G. Ferraro strictly limits his inquiries to his native area of Carpeneto, in Upper-Monferrato, Province of Alexandria.

One might think that only Piedmont, of all Italian regions could boast genuine narrative songs. This is not correct:

A Venetian "canzone" made up of quatrains of ten-syllable verses rhyming two by two was committed to writing three times. The prose synopsis published by the Venetian Luigi Carrer in 1838 in "Prose e poesie", IV is one of the first written record of the "concealed death" folk tale topic.

The song of "Count Azolin" was then collected in Vicenza by Georg Widter and published in 1864 in his "Volkslieder aus Venetien".

Giuseppe Ferraro came across the same character whose name was defaced to "Cagnolino" at Pontelagoscuro, in Piedmont in theprovince of Ferrara.

Antonio Ive, in his "Canti popolari istriani" published in 1877, printed a song collected in Rovigno in Istria (known nowadays as Rovinj) recounting the sad story of Count Angiolino.

None of these texts unfortunately is accompanied by a musical record!

The story is roughly the same in the three songs. Here is part of the translation of "Count Anzolin" by Sophie Jewett (1913):

"0 little daughter, more than my daughter, 'Tis only for the pilgrims who come from Rome today." "O my love's mother, more than my mother. Why are thy dear eyes weeping tears alway?" "0 little daughter, more than my daughter. It is only the chimney that will be smoking still." "O my love's mother, more than my mother. Why do the servants cry so loud and shrill?" "0 little daughter, more than my daughter. It is because the best of all our steeds has died. " "O my love's mother, more than my mother, Why does Count Anzolin not come to my bedside?" "O little daughter, more than my daughter, The Count Anzolin has ridden to the chase." "O my love's mother, more than my mother, To go to the church, what gown were most in place?" "Wear the gown of rose, or wear the gown of white, dear. Yet perhaps the gown of black is fitter than the white." ' ' Like a bride I will dress me in the gown that 's fairest, Not like a little widow in weeds as black as night. "O my love's mother, more than my mother, Why are all the people staring as I pass?" "O my little daughter, more than my daughter, They are always staring when ladies go to mass. "

|

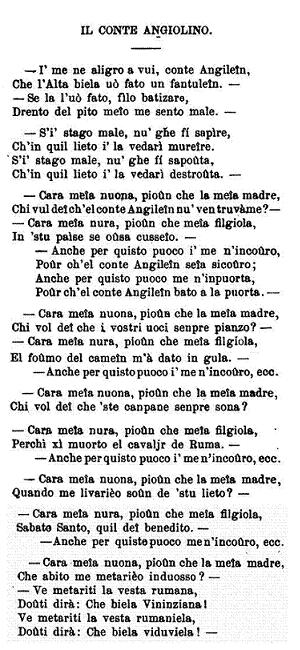

2. IL CONTE CAGNOLINO (Agnolino).

Questo canto è insieme canta e rappresentazione,

il Conte Cagnolino si voleva ammogliare, ma non voleva

che la sua futura sposa avesse fatto V amore con qual-

cun altro prima. Nel suo giardino aveva una statua di

marmo, la quale moveva gli occhi, quando le si presen-

tavano dinanzi ragazze che avessero fatto all'amore. In-

fatti il Capitano Tartaglia avendo offerto sua figlia al

Conte Cagnolino, costei colle compagne diceva:

Quando verrà quel fortunato giorno.

Che me ne potrò star sopra quel soglio

E possa dir : posso, comando e voglio ?

ma condotta davanti la statua è dichiarata una civetta, ed

il Conte Cagnolino sposa la figlia del Dottor Balanzone,

che è approvata dalla statua. Il Capitano Tartaglia giura

la morte del Conte Cagnolino, e lo uccide in una caccia,

quindi succede il seguente dialogo fra suocera e nuora:

— Mama, la miè mama,

Cos' hal al servitor che pianze tanto? —

- Norina, che si più che me fijola,

Al pianz che ha perso al so cavai spagnardo. -

- Mama, la mie mama,

Quando me menla a messa? —

- Norina, che sì più che me fijola,

Vi menarò la zobia di san Marco. —

- Anca di questo poco me ne curo.

Che 'l Conte Cagnolin ben m' è sicuro, —

- Norina, che sì più che la mia mama,

Cos' ha quei occì che èn tanto pianzenti? —

- Norina che sì più che me fijola,

L' è stat al fum ch' è nella cusina. —

- Norina, che sì più che la mìa mama,

Qual abit mi gh' ho mai da metar ! —

- Norina, che sì più che me fijola,

Con quel nègar vu pari pur bona. —

- Norina, che sì più che la mia mama,

Cos'ha la zent che tutti tant am guarda? —

- Norina, che sì più che me fijola,

Iv guarda parchè vu sì mo levada. —

- Norina, che sì più che la mia mama,

Cos' ha quell'arca ch' è verta da fresco ? —

- Oh questo pò ve lo devo ben dire.

Conte Cagnolin l'ho fatt sepelire. —

- Norina, che sì più che la mia mama.

Al me putin a vu lo raccomando.

Con de la carta felo un Dottore,

Con di bei pagn felo un Professore;

E mi andarò col mio amor.

Da zà che lu l'è mort, l'è fatt al mie destin:

Me ne vojo andar dal Conte Cagnolin. -

Pontelagoscuro: G. Ferraro: "Canti popolari di Ferrara,

Pontelagoscuro e Cento", 1877, page 84

|

Vicence: Adolf Wolf, "Volkslieder aus Venetien", p.62, 1864

|

Rovigno: Antonio Ive, "Canti popolari istriani", p.344, 1877

Giuseppe Ferraro (1845-1907)

|