Ar Pec'hour

Le Pécheur

The Sinner

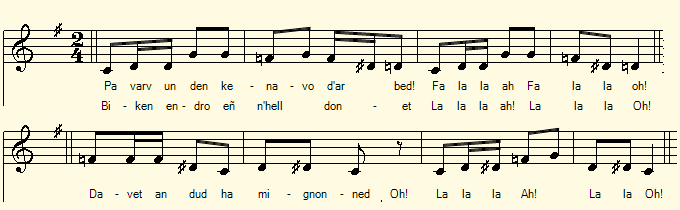

Chant tiré du 2ème Carnet de collecte de La Villemarqué (pp. 14-16).

Mélodie

"Endro"

Arrangement Christian Souchon (c) 2010

|

A propos de la mélodie Exceptionnellement La Villemarqué a noté pour ce chant des onomatopées qui alternent avec des phrases faisant sens. En regroupant les indications de la page 14, on peut, semble-t-il, reconstituer la structure du poème: des strophes de 3 vers de 8 pieds alternant avec des "la, la, la" qui, malgré le sujet sérieux, évoquent un rythme de danse, et plus spécifiquement celui de l'en-dro ("mod koz", ancienne mode), à condition de répéter le 3ème vers: 4 mesure à 2 temps (cf. Musique -En dro). On peut pennser à l'endro ci-dessus qui a été noté en 1953 par J.-M. Guilcher à Guidel, sous la dictée de Y. Béchenec ("La Tradition populaire de danse en Basse-Bretagne", p. 313) . Comme on le sait, l'utilisation de cantiques était une pratique courante chez les missionnaires tels que Michel de Nobletz ou Julien Maunoir qui n'hésitaient pas à recourir à des chansons populaires, voire gaillardes pour faciliter la mémorisation de leur enseignement (cf. An Ivern et An baradoz). A propos du texte Le dialecte du barde ou du chanteur n'est pas le bas-cornouaillais de Nizon, mais ressemble fort au vannetais, Des points de suspension entre certaines strophes signalent peut-être des passages oubliés par le chanteur ou négligés par le collecteur. |

About the tune Exceptionally La Villemarqué noted for this song onomatopoeia that alternate with meaningful sentences. By rearranging the hints recorded on page 14, we should be able to restore the structure of the poem: stanzas of 3 verses of 8 feet alternating with sets of "la, la, la" which, despite the serious subject, evoke a dance, and more specifically the "en-dro" rythm known as "mod koz" (old fashion), if the 3rd verse is repeated: 4 two-beat measures (see Musique - Endro. We may think of the above "En-dro" which was noted in 1953 by J.-M. Guilcher at Guidel, from the singing of Y. Béchenec (in "The Popular Dance Tradition in Lower- Brittany ", p. 313). The use of hymns was a common practice among missionaries such as Michel de Nobletz or Julien Maunoir who did not hesitate to resort to popular or even bawdy songs to make their teaching easier to remember (see An Ivern and Ar baradoz ). About the lyrics The dialect used by the bard or the singer is not, as is usual in the Barzhaz, the Quimper dialect spoken in Nizon. It looks very much like Vannes dialect, Suspension points between certain stanzas could hint passages forgotten by the singer or skipped by the collector. |

|

BREZHONEG (Stumm KLT) P. 14 Ar Pec'hour 1. Pa varv un den: kenavo d'ar bed! Fa la ah! / Fa la la o! Biken endro eñ n’hell donet Fa la la ah! /. Fa la la o! Davet e dud ha mignoned, [O!] Fa la la ah! / Fa la la o! [bis] 2. Ne vern e-men e vez lojet, Peger gras-vad, pegen desped. Dalc’hmat, eno chom e vo red. Fa la ah!. la la ah! / la la ha la la ha 3. Ar c'hwibuenn lec'h ma kouezho, La la la la/ la la ah! la la Birviken ac'hann ne zavo, La la / la la / la la / la la ah! Na cheñchamant ebet n’en-do. p. 15/8 4. Ha doc'h ma vo bet ma buhez, M’em-bo an holl eternite ’N neñv, pe ‘n ifern evit gwele. 5. Goude em- bo em rudellet D'el loustoni hag d'ar pec'hed, Petra am- bo me gounezet? 6. Me a gav aon rak daonasion, Disesper ha perdision A c'hounez kentoc'h ma c'halon. 7. Evit c'hoantegezh lik, brutal, (dirujel) Doc'h al loened e fer heñval, Hep komz ag an drougoù arall. 8. En tavernioù en em foeter, Evel chas en em zispenner Hag hep kristenezh e fever . 9. Er c'hoarzhad (c'hoarzhin) kaer en em gweler "Un den laouen on“ e larer, Nec'h drouk ann diaoul a zo pounner. - p. 16 10. Pec'hour on bet, c‘hoazh e pec'han Me zant ur pik, ennon zantan Me gred gwelout [?] an diaoul em hun. . . . . . . . . . . 11. Ret eo ta, Kristenien, evit mat, Distroiñ oc'h Doué, ha kuitaat. An diaoul, ar c'hig hag an ebat. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12. Madalen oc'h eus pardonet Hag al laer mat oc'h euz salvet. Rag o c'halon a oa cheñchet. . . . 13. Cheñchit ivez ma c'halon-me. Keit da ouelan ma fall vuhez. Me varvin en Ho karantez. KLT gant Christian Souchon |

FRANCAIS P. 14 Le pécheur 1. Quand l’homme meurt, au monde adieu! Fa la ah/ la la la o! Revenir jamais il ne peut La la ha/ la la o!. Vers ceux qu’il a jadis aimés, O! La la / la la/ la la/ la la o! [bis] 2. Quel que soit son dernier logis, De bonne grâce ou malgré lui, Il y restera pour jamais, Fa la ah!. la la ah! / la la ha la la ha 3. D’où le moucheron est tombé La la la la/ la la ah! la la C’est en vain qu’il veut s’envoler; La la / la la / la la / la la ah! Non, jamais il n’y parviendra. p. 15/8 4. Et selon ce que fut ma vie, L’éternité m’est impartie, Enfer ou ciel selon le cas, 5. Je me suis tout ce temps vautré Dans le stupre et dans le péché. Aurais-je ainsi fait mon malheur? 6. Oui, j ai peur de la damnation. Le désespoir et l’affliction Ont tôt fait de ronger mon cœur. 7. Un intinct lubrique et brutal Nous ravale au rang d’animal Pour ne rien dire d’autres maux. : 8. Au cabaret l’on se dissipe Et comme des chiens l’on s’étrippe. Et « chrétien » n’est plus qu’un vain mot. 9. On se perd en plaisanteries On est « de bonne compagnie ». Mais on a grand peur de Satan. p. 16 10. J’étais pécheur, je pèche encor. Je sens l’aiguillon dans mon corps Crois voir le diable quand je dors. . . . . . . . . 11. Il faut donc, Chrétiens, pour de bon, Retourner à Dieu. Le démon, La chair, le monde ont fait leur temps. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12. Madeleine fut pardonnée L’âme du larron fut sauvée Car ils sont su se repentir. 13. Changez aussi le cœur en moi, Ma vie mauvaise me déçoit ; En Votre amour je veux mourir. Traduction Christian Souchon (c) 2019 |

ENGLISH Page 14 The Sinner 1. Once you said to the world goodbye, Fa la la ah! / La la la o! You never come back, when you die, La la la ha / la la la o! How much your kith and kin may cry. La la / la la/ la la/ la la o! [twice] 2. Whatever your last dwelling was Worth of disdain or of applause, From his last place no one withdraws. Fa la ah!. la la ah! / la la ha la la ha 3. A gnat landing on sticky stuff, La la la la/ la la ah! la la Try as it may, it won’t fly off. La la / la la / la la / la la ah! And Fates at its endeavours scoff. p. 15/8 4. Was or was not your life holy, Your bed in all eternity Will be Heaven, or Hell only. 5. I have wallowed a whole lifetime In debauchery’s muddy brine. Now I fear the reward of crime. 6. I am afraid of damnation. I feel despair, and affliction Gnaws at my heart. No remission. 7. Most lustful and brutal impulse Have lowered us to animals, Not to mention other evils. 8. In the pubs we scuffle and fight And like dogs, each other we bite, Though claiming to be Christian wight. 9. And oft I was seen having fun, Proud to be a choice companion: In fact I was scared of Satan. p. 16 10. I was a sinner, I still sin. I feel in my body a sting A devil stirs: what awful thing! . . . . . . . . 11. Christians, you should truly return To God, get rid of Devil’s spurn, Flesh, all kind of mundane concern! . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12. God forgave Mary Magdalene And the good thief’s soul was made clean: The repentance both showed was keen. 13. O my God, change this soul of mine! My loathsome past life I resign. May my dying heart be Thy shrine! Translated by Chr. Souchon |

NOTE

|

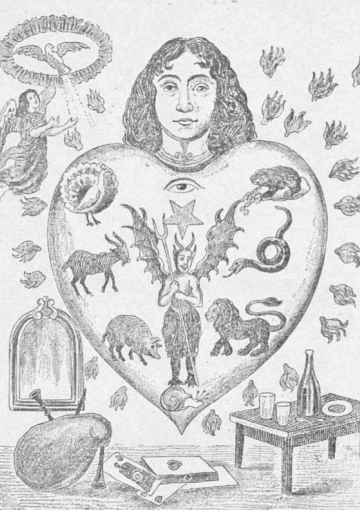

Ce texte énonce un article de foi dont on peut douter qu'il soit très orthodoxe: quels que soient ses antécédents, l'âme va au ciel ou en enfer selon l'état de sainteté ou de péché au moment précis où la mort la surprend. Il ne semble pas que ce texte ait été noté par aucun autre collecteur. En particulier, on ne trouve rien de semblable dans les "Kanaouennoù santel evit Eskopti Kemper" (Cantiques pour l'Evêché de Quimper) publiés en 1842 par l'Abbé Henry (1803-1880), bien que ce recueil contienne quelques chants du Barzhaz Breizh. La réthorique développée dans le présent chant ressemble fort à celle dont s'inspirent les commentaires des "taolennoù" ou "tableaux de mission" de Michel Le Nobletz (1577-1652) et de Julien Maunoir (1606-1683). Dans ces tableaux on ne voit que la tête et le cœur, soit les deux aspects de l’homme : le corps et l’âme. Lequel des deux a le plus d’importance? Les tableaux répondent en vérité, sans détour: l'âme bien sûr! (cf. http://www.pdbzro.com/pdf/balanant_animaux.pdf) |

"Un ene e stad a bec'hed marvel" Une âme en état de péché mortel Tiré de "Tableau de Mission expliqué par l'abbé Balanant", Quimper, 1899. |

This text sets forth an article of faith which should hardly be very orthodox: whatever its antecedents, the soul goes to heaven or to hell, depending on the state (holiness or sin) it was in, at the precise moment when the death surprised it . It does not appear that this text was recorded by any other collector. In particular, there is nothing similar in the "Kanaouennoù santel evit Eskopti Kemper" (Hymns for the Bishopric of Quimper) published in 1842 by Abbé Henry (1803-1880), although this collection includes some Barzhaz Breizh songs. The rhetoric developed in the present song is very similar to that inspired by the comments of the "taolennoù" or "mission charts" devised by Michel Le Nobletz (1577-1652) or Julien Maunoir (1606-1683). In these paintings we see only a head and a heart, the two aspects of man: the body and the soul. Which of the two is most important? The painting's answer is straightforward: the soul of course! (see http://www.pdbzro.com/pdf/balanant_animals.pdf) |