Ar brezelour yaouank

Le jeune combattant

The young warior

Chant tiré du 2ème Carnet de collecte de La Villemarqué (p. 256 - 258).

Mélodie

Arrangement Christian Souchon (c) 2020

|

A propos de la mélodie Inconnue. Celle retenue ici permet de regrouper les distiques quatre par quatre et son caractère solennel convient au texte empreint de mysticisme. A propos du texte Seul La Villemarqué a collecté ce beau chant, semble-t-il. La mention du chanteur, Laurent Le Sauz de Brennilis, suivie de la date exacte, permet de constater qu'un écart d'une vingtaine d'années sépare la collecte de ce chant de celle du précédent sur notre liste, La soupe au lait, p.221 / 132, dont 2 strophes apparaissent dans le Barzhaz de 1845, dans le chant "La ceinture de noces. C'est en 1863 également que furent collectées les 2èmes versions de "L'abbé de Kersalaün", p.251 et, logiquement, de la Chanson du marchand, p.254, qui lui fait suite. Dans une lettre du 2 novembre 1879, Emile Ernault écrit que, lors d'une visite à Keransquer, La Villemarqué lui avait montré ses cahiers d'enquête, lui avait lu une chanson "qui avait bien l'air d'être un appel à la croisade... Il doit s'agir de la présente pièce. Ce qui apporterait un démenti à Francis Gourvil qui cite cette lettre, p. 260 de sa thèse sur "La Villemarqué" (1959) et affirme qu'elle "n'est, hélas, qu'une curiosité de plus dans [cette] affaire...". |

About the melody Unknown. The sound background chosen here made it possible to group the stanzas four by four and it is likely to match the solemn character of the lyrics imbued with mysticism. About the text Only La Villemarqué apparently did collect this beautiful song. The mention of the singer, Laurent Le Sauz of Brennilis, followed by the exact date, hints at a gap of twenty years between the collecting of this song and that of the previous on our list, La soupe au lait , p.221 / 132, of which 2 stanzas appear in the 1845 Barzhaz as parts of the song "The wedding belt . It was also in 1863 that the 2nd versions of "The Abbé of Kersalaün" , p.251 and, logically, of the ensuing Song of the Merchant, p.254, were recorded. In a letter dated November 2, 1879, Emile Ernault wrote that, during a visit to Keransquer, La Villemarqué showed him his record notebooks and especially a song "which sounded like a call for a crusade ... This could refer to the present piece and bring a denial to Francis Gourvil who quoted this letter on p. 260 of his doctoral thesis on "La Villemarqué" (1959) and asserted that it "was, unfortunately, but another weird oddity in this strange case ...". |

|

p. 256 Ger diwezhañ ar brezelour yaouank En marge à gauche verticalement: Chant de départ d’un Croisé? [1] (Le 18 septembre 1863: chanté par Loranz ar Saoz de Brennilis) ********* 1. An Aotrou But (?) (An den yaouank) a Vreizh-Izel, Zo aet er bloaz-mañ d'ar brezel. 2. Eizh(ve)tez kentañ , eizh(ve)tez goude (kent deiz), E vreur, e c'hoar d'e(zh)añ lavare : 3. - Ma breurig paour, chomit er gear, Na da ziwallat (Chomit da ziwall) hon douar! 4. Hon douar piv hen diwallo? - Nep hen ziwall , nep a hallo! 5. Chom er ger, ma c'hoar, n'hallan ket: (Allas, ma c'hoar, ne hallan ket) Mont da heul an Duk a zo ret. 6. Roit d'ar beorien ma lod madoù, Rak ma danvez zo en neñvoù! p. 257 7. Menez Kalvar, me oar er-vat, [2] A zo bet sommanet (?) d'ar gad. (?: assigné - renvoyé à) 8. Abaoe, m'on deuet da gompren: Ar bed-mañ n'eo 'met un tremen. Strophe insérée au crayon: 9. Ar bed-mañ a zo ken tretour Evel d'ur bleuñv war an dour. [3] (Evel ar c'houmon eus ar mor.) 10. Me wel ac'han d'eus ma gwele Ur wezenn plantet ganin-me ('vidon-me.) 11. He delioù a zo alaouret Hag he bleinioù (extrémités) zo arc'hantet. 12. Ha m'hen glev o skuilhañ daeroù Poken (takenn) ha poken he delioù. 13. He gwrizioù a zo liv d'ar gwad D'ar gwad a zo m'hini, m'oar vat, Eno 'maon sommanet d'ar gad. 14. Ur morvran d'eus an enezenn Mor-c'hagnaouer d'eus hon enezenn (?) A laer ar frouez d'eus ma gwezenn. 15. Abaoe m'on deuet da gompren: Un trait amène ce vers apres : 'Vidon-me eo plantet ar we(z)enn] p. 256 16. Kenavo! Mont a ran d'an hent, An eskibien, ar veleien, Ha Jesuz Krist, ganeomp, er penn! (1) = (1) Note de La Villemarqué en bas de page: Peut-être s'agit-il d'un Budes (Hervé), je crois.(1247) dans cette pièce. Il portait d'or, à l'arbre de pin de sinople accosté de deux fleurs de lys de gueules. [4] KLT gant Christian Souchon (c) 2020 |

p. 256 Les derniers mots d'un jeune guerrier En marge à gauche verticalement: Chant de départ d’un Croisé? [1] (Le 18 septembre 1863: chanté par Laurent Le Sauz de Brennilis) ********* 1. Le seigneur But (?) (An den yaouank) un Bas-Breton, Partit cette année pour la guerre. 2. La semaine précédant son Départ sa pauvre soeur, son frère 3. Disaient: - Restez à la maison, Restez défendre notre terre! 4. Qui donc la défendra, sinon? - N'importe qui pourra le faire. 5. Ma soeur, je ne resterai point. (Hélas, ma soeur, je n'y peux rien.) Quand le Duc part, il faut le suivre. 6. Aux pauvres distribuez mes biens, Car au ciel, j'aurai de quoi vivre. p. 257 7. Le mont Calvaire, à ce qu'on dit, [2] Est l'enjeu (?) de luttes sauvages. (?: assigné - renvoyé à) 8. Et il m'est apparu depuis: Que ce monde n'est qu'un passage. Strophe insérée au crayon: 9. Ce monde va de ci, de là Comme une fleur sur la rivière. [3] (Tel le goëmon sur la vague.) 10. Je contemple depuis mon lit L' arbre que j'ai planté moi-même: (pour moi-même) 11. Son feuillage d'or resplendit. L'argent brille en ses bords extrèmes. 12. Il verse des pleurs, je l'entends. Ces feuilles! On dirait des gouttes 13. Qui baignent sa souche de sang! Et ce sang c'est le mien, sans doute! Moi qu'à cette guerre on conduit... 14. Un cormoran venu de l'île Un charognard venu de l'île (?) De mon arbre vole les fruits. 15. Chut! Plus un mot! C'est inutile. Un trait amène ce vers après : Cet arbre fut planté pour moi. p. 256 16. En route il faut que je me mette, Evêques et prêtres en tête Vont, portant Jésus sur Sa croix! (1) = (1) Note de La Villemarqué en bas de page: Peut-être s'agit-il d'un Budes (Hervé), je crois.(1247) dans cette pièce. Il portait d'or, à l'arbre de pin de sinople accosté de deux fleurs de lys de gueules. [4] Traduction Christian Souchon (c) 2020 |

p. 256 The last words of a young warrior Left margin vertically : Starting song of a Crusader? [1] (September 18, 1863: sung by Laurent Le Sauz de Brennilis) ********* 1. Sir But (?) (A young man) from Lower-Brittany, Will go to war before year's end. 2. Which, before he leaves, steadfastly His sister, his brother contend: 3. - My dear brother, please, stay at home, Stay at home. This estate needs you: 4. Would be protected by no one! - That's a thing anyone can do. 5. Sister, how could you wish I stayed (Alas, sister, I can't help it) When the Duke leaves, I must follow. 6. Distribute to the poor my goods! In Heaven's riches I'll wallow. p. 257 7. Mount Calvary, so I was told, [2] Is at stake (?) in a bloody fray. (?: assigned - referred to) 8. It occurred to me that this world Is no place forever to stay. Stanza inserted in pencil: 9. This lesser world turns to and fro As white pond water lilies do. [3] (Like seaweed floating on the wave) 10. Lying in my bed, I can see - I planted it myself -(T was planted for myself) a tree: 11.Gold spots in its foliage glitter And it is outlined in silver. 12. It is crying, as I can hear And each leaf it drops is a tear. 13. All these tears tint its roots blood red, Red like the blood that I shall shed On the fields whither I am led. 14. A cormorant from the islands A scavenger from the islands (?) From my tree is stealing the fruits. 15. Shhh! Not a word! It is no use, A line points to the sentence: The tree's for me. It's obvious p. 256 16. Farewell! The host draws near. It's led By bishops and priests and ahead Of us all, Jesus on the Cross! (1) = (1) Footnote by La Villemarqué: "Maybe the song is about a named Budes (Hervé), who lived, I take it, (in 1247). His coat of arms had, on a golden background, a green pine tree surrounded by two red fleurs-de-lis." [4] Translation: Christian Souchon (c) 2020 |

NOTES

|

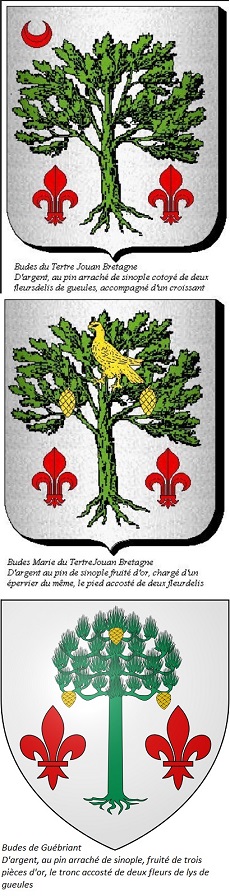

[1] Croisé ?: Une remarque interrogative en marge, "Chant de départ d'un Croisé?", montre qu'en 1863, La Villemarqué s'est assagi. Il aurait été plus affirmatif 20 ans plus tôt. [2] Mont Calvaire: L'évocation à la strophe 7 du Calvaire qui a été "sommanet d'ar gad", ce qu'il traduit lui-même par "assigné" ou "renvoyé", "d'ar gad" signifiant "au combat", fait effectivement penser à ce type d'événement. Le mot "duk" (Duc) à la strophe 5 renvoie à la Bretagne ducale et le cortège de la strophe 16, en tête duquel marchent des évêques et des prêtres porteurs d'une croix, peut tout à fait être celui d'un départ de croisade. Il en est de même de la strophe 6 où le vers "rak ma danvez zo en neñvoù" (car ma fortune est aux cieux) évoque peut-être les récompenses spirituelles et les indulgences que le Pape attachait à la participation à ces guerres contre les hérétiques. Cependant le mont Calvaire apparaît dans d'autres gwerzioù, par exemple celle du Moine Guillaume Le Gall et Les trois Marie auxquelles on ne saurait attribuer une telle antiquité. Or la période des croisades va traditionnellement de 1095 à 1291, du concile de Clermont-Ferrand à la prise de Saint-Jean-d'Acre. Il est vrai que des opérations militaires sous l'égide de la papauté ont eu lieu jusqu'à la bataille de Lépante en 1571. [3] La fleur et l'arbre: Il en va de même de la figure de la fleur de nénuphar aux mouvements erratiques et de celle de l'arbre destiné à fournir les planches du cercueil où reposera le héros de l'histoire (cf. Le lépreux, strophes 11 et 12, et Les soldats vont de rouge vêtus). Ces réminiscences, ainsi que l'allure générale du poème (la romantique image des feuilles d'automne qui ressemblent à des gouttes de sang) suggèrent une oeuvre de la fin du 18ème ou du début du 19ème siècle. Peut-être est-elle à ranger parmi les compositions des prêtres et des clercs acquis à la cause chouanne, auquel cas l'armée où les prêtres et les évêques marchent en tête serait l'Armée royale et catholique. Le "duc" pourrait être un aristocrate influent dont le héros, un aristocrate également, (Seigneur But) suivrait les incitations à la rébellion. La mention du Mont Calvaire devenu champ de bataille, serait une allégorie du soulèvement chouan. [4] Sire But: Dans la note (1), en bas de la page 256, La Villemarqué suggère une interprétation tout à fait plausible du nom "But": Il pense qu'il s'agit d'une évocation de la famille noble Budes de Guébriant d'extraction féodale, originaire de Bretagne, dont la filiation est suivie depuis le milieu du 13 siècle. Elle fut maintenue noble en 1670 devant le Parlement de Bretagne à Rennes. La Villemarqué pense que le "Seigneur But" de la strophe 1 est de l'ancêtre éponyme de cette famille, Hervé Budes qui partit à la croisade en 1247. Cette gwerz, selon La Villemarqué, a la particularité vraiment unique de décrire un blason. Il note: " Il portait d'or, à l'arbre de pin de sinople [vert] accosté de deux fleurs de lys de gueules [rouges].". On peut objecter que l'arbre décrit aux strophes 10 à 13, est un arbre doré à feuilles caduques qui se détache sur un fond d'argent. Mais l'arbre vert des Budes s'orne, sur les blasons de certaines branches de cette famille de trois pommes de pin dorées. Les feuilles mortes qui donnent aux racines de l'arbre la couleur du sang sont peut-être évoquées par les deux fleurs de lys de part et d'autre du "pin arraché de sinople" où le rouge remplace l'or de l'emblème royal. Le "cormoran (ou le charognard) venu de l'île" qui vole les fruits pourrait évoquer l'épervier d'or qui orne les armes des Budes descendants de Marie du Tertre-Jouan. Quant aux Budes du Tertre Jouan de Bretagne, leurs armes comportent un croissant qui rappelle peut-être leur ancêtre croisé. Le personnage le plus illustre de cette famille, tout au moins avant la Révolution, fut Jean-Baptiste Budes de Guébriant (1602-1643), maréchal de France, comte de Guébriant qui mourut au siège de Rottweil en Bavière, pendant la guerre de Trente Ans, le 24 novembre 1643. [5] La restauration des chapelles décorées par Viollet-le-Duc après l'incendie de Notre-Dame en 2019 permet d'admirer à nouveau, le monument funéraire de Jean-Baptiste Budes de Guébriant, mort la même année que le roi Louis XIII. L'inscription en latin nous apprend que celui-ci le destinait à être le précepteur du dauphin (Louis XIV). On reconnait sur le monument son blason à l'arbre vert. Son épouse, Renée du Bec-Crépin fut inhumée en 1659 dans cette prestigieuse chapelle. |

[1] Croisé : The interogative remark in the left margin, "Song of departure of a Crusader?", clearly shows, that in 1863, La Villemarqué had calmed down quite a bit. He would have been more peremptory 20 years earlier! [2] Mount Calvary : The evocation in stanza 7 of Mount Calvary that was "sommanet d'ar gad", which he himself translates as "assigned" or "agreed upon", "ar gad" meaning "as a battlefield", may actually evoke this kind of event. The word "duk" (Duke) in stanza 5 could refer to "Ducal Brittany" and the procession in stanza 16, at the head of which bishops and priests carrying the Cross were marching, actually suggests the start of some crusade. The same applies to stanza 6 where the line "rak ma danvez zo en neñvoù" (for my fortune is in Heavens) perhaps evokes the spiritual rewards and indulgences promised by the Pope to all those taking part in these wars against heretics. However, Mount Calvary appears in other gwerzioù, for example that of Monk Guillaume Le Gall and The three Marys to which we cannot ascribe such great antiquity. However, the period of the Crusades traditionally goes from 1095 to 1291, from the Council of Clermont-Ferrand to the capture of Saint-Jean-d'Acre, though military operations under the aegis of the papacy took place until the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. [3] The flower and the tree : The same applies to the figure of the water lily flower with erratic movements and that of the tree that was planted to provide the planks for the coffin where the hero of the story once will be laid (cf. The leper , stanzas 11 and 12, and Soldiers dressed in red ). These reminiscences, as well as the general allure of the poem (the romantic image of autumn leaves resembling drops of blood) suggest a work of the end of the 18th or the beginning of the 19th century, which would rank among the works of priests and clerics supporting the Chouan cause , in which case the army where the priests and bishops march in front would be the Army royal and catholic . The "duke" could be an influential aristocrat whose incitements to rebellion the hero of our song, also an aristocrat, (Lord But) would follow. The mention of Mount Calvary which was to become a battlefield would be an allegory of the Chouan uprising. [4] Sir But : In note (1), at the bottom of page 256, La Villemarqué suggests a very plausible interpretation of the name "But". It could be an ancestor of the noble family Budes de Guébriant of feudal extraction, originating in Brittany, whose lineage can be followed since the middle of the 13th century. It was kept noble in 1670 by order of the Parliament of Brittany in Rennes. La Villemarqué thinks of the eponymous ancestor of theis family, a named Hervé Budes who lived in 1247. In addition, this gwerz would have the truly unique characteristic of describing a coat of arms : "It bore gold, on a green the pine tree surrounded by two red fleur-de-lis." . One may object that the tree described in verses 10 to 13, is a deciduous golden tree, which stands out against a silver background. However the green tree of the Budes is adorned, most often, with three golden pine cones. The dead leaves which give the roots of the tree the colour of blood are perhaps evoked by the two fleurdelis on either side of the green pine where the red replaces the gold on the royal coat of arms. The "cormorant (or scavenger) come from the island" that steals the fruit could refer to the golden hawk that the coats of arms of the Marie du Tertre-Jouan branch of the Budes family feature. As for the Budes du Tertre Jouan de Bretagne, their arms have a crescent which is perhaps reminiscent of their crusader ancestor; The most illustrious character of this family, at least before the Revolution, was Jean-Baptiste Budes de Guébriant (1602-1643), Marshal of France, Count of Guébriant who did not participate in any crusade, but died at the siege of Rottweil in Bavaria, during the Thirty Years' War, November 24, 1643. [5] The restoration of the chapels decorated by Viollet-le-Duc after the fire at Notre-Dame in 2019 allows us to admire once again the funerary monument of Jean-Baptiste Budes de Guébriant, who died the same year as King Louis XIII. The Latin inscription tells us that the latter intended him to be the tutor of the Dauphin (Louis XIV). His coat of arms with the green tree can be recognized on the monument. His wife, Renée du Bec-Crépin, was buried in 1659 in this prestigious chapel. |

|

|

|

|

|

|