Ar C'hemener - Kemeneur

Le tailleur

The tailor

Chant collecté par Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué

dans le 2ème Carnet de Keransquer (pp. 88-89).

"Ar c'hemener"

Arrangement MIDI Christian Souchon (c) 2020

|

A propos de la mélodie Ce chant a été souvent collecté. Le timbre qui l'accompagne est donné par plusieurs documents: C'est ainsi qu'une feuille volante publiée par l'imprimeur morlaisien Alexandre Ledan (1777-1855) et un de ses manuscrits reproduits dans le volume 1 du recueil "Gwerzioù, chansonioù ha rimoù brezhonek", p. 435-437, intitulent ce chant (a) "Ar c'hemener" et portent l'indication "Var ton: calz a amzer am eus collet" (sur l'air de "J'en ai perdu du temps"). Sur notre site, cette mélodie est donnée avec le chant homonyme à la page Kalz a amzer am-eus kollet. Le site dédié aux "Chansons de tradition orale en langue bretonne dans les livres, revues et manuscrits" (https://to.kan.bzh/chant-00644.html#) donne au présent chant la référence M-00644 du catalogue Malrieu. Il fait état, pour cette version de 9 strophes, reprise par Pierre Lanoé, le successeur de Lédan, dont l'activité va de 1881 à 1895, d'une collecte effectuée avant 1815, sans toutefois justifier cette date. C'est de ce site que sont issues pour l'essentiel, les informations données ci-après. On y mentionne 11 versions différentes et 18 occurrences, auxquelles il faut donc désormais ajouter la présente version, (b) "Kemeneur", collectée par La Villemarqué en 1840-1841. Les autres occurrences sont plus récentes: - (c) "Sonenn er hemener" (vannetais) dans "Sonamb get en Drouzerion", tome II de Fañch Desbordes, collecteur Jorj Belz, 1985. - (d) "Sonen ar c'hemener" dans "Poésies populaires de France, Manuscrits 3338 à 3343" de Victor Bléas, collecté avant 1854 (dans le cadre de l'enquête Salvandy-Fortoul). Cette version est presque identique à (a). - (e) "Son ar c'hemener", mélodie collecté avant 1913 à Ploëzal par François Vallée, reproduit, avec 1 variante vannetaise de "Kalz a amzer" dans "Musiques Bretonnes" de Maurice Duhammel (chants 412 et 413, p.210). Les paroles de référence sont celles recueillies par Luzel. - (f) "Zon ar c'hemener" dans les "Soniou Breiz-Izel" de F-M. Luzel (T.2, pp.234-237), collecté avant 1980 à Plouëc de Trieux. - (g) "Pa ' c'ha 'r c'hemener d'he labour" collecté en 1890-1909 à Penvenan par Anatole Le Braz. (Cité par Tanguy dans "Anatole Le Braz et la tradition Populaire en Bretagne, 2, 63). - (h) "Ar c'hemener" collecté en 1989 (CD), puis en 1995 à Trédarzec par Ifig Le Troadec, publié dans "Carnets de route", 2005 avec notation musicale. Le fond sonore de la présente page alterne les deux mélodies publiées par Maurice Duhammel. A propos du texte Dans l'argument qui précède le chant Les Nains dans le Barzhaz de 1839, La Villemarqué suggère quelques explications à l'exécration des tailleurs qui s'exprime ici avec une telle méchanceté : "Cette classe [était jadis] vouée au ridicule, en Bretagne ... et ailleurs, ...chez toutes les nations guerrières, dont la vie agitée et errante s’accordait mal avec une existence casanière et paisible." Ceci dit, le mépris qu'éprouvaient les paysans à l'égard du tailleur s'alimentait à plusieurs sources:

On trouve cette même strophe dans le chant Loiza I, strophe j, noté page 257 du carnet N°1 qui aurait dû entrer dans la composition d'un chant du Barzhaz, "La Quenouille", sans l'intervention malencontreuse de Luzel. Il existe même une variante encore plus humiliante de cet anathème:

C'est sans doute la feuille volante de Lédan qui a contribué à diffuser le thème du tailleur, lie du genre humain, dans la tradition populaire. Pourtant, ni la feuille volante qu'il a publiée, ni son manuscrit ne portent son nom, comme c'est habituellement le cas pour ses compositions. Lédan a sans doute recopié un chant ancien ou fait la synthèse de plusieurs versions. C'est ce que confirmerait la présence d'une strophe du "Tailleur" dans le "Cygne", un chant vraisemblablement relatif à un événement de 1379. On peut supposer que la version notée par La Villemarqué, avec les éléments qui lui sont "propres", le "pet dans un tapis", le" voleur de retailles", le "repas dans l'auge à cochons", est indépendante de la version Lédan. Peut-être a-t-elle même été notée antérieurement à celle-ci... |

About the tune This song was often collected. The tune to which it should be sung is specified in several documents. For instance, a broadside sheet published by the Morlaix printer Alexandre Ledan (1777-1855) and one of his manuscripts included in volume 1 of the collection "Gwerzioù, chansonioù ha rimoù brezhonek ", p. 435 - 437, title this song (a) "Ar c'hemener" with the hint: "Var ton: calz a amzer am eus collet" (to the tune of "I have wasted much time"). On our site, this melody is given with the homonymous song on the page Kalz a amzer am-eus kollet. The site dedicated to "Songs of oral tradition in the Breton language in books, magazines and manuscripts" (https://to.kan.bzh/chant-00644.html#) references this song as M-00644 in the Malrieu catalog. It records a 9 stanza version, also published by Pierre Lanoé, Lédan's successor, whose activity goes from 1881 to 1895, allegedly collected before 1815, without however justifying this date. Most of the below information is borrowed from this site. It mentions 11 different versions and 18 occurrences, to which we should now add the version at hand: (b) "Kemeneur", collected by La Villemarqué in 1840-1841. As for the other occurrences, they should be more recent: - (c) "Sonenn er hemener" (vannetais) in "Sonamb get en Drouzerion", volume II by Fañch Desbordes, collector Jorj Belz, 1985. - (d) "Sonen ar c'hemener" in "Poésies populaires de France, Manuscrits 3338 to 3343" by Victor Bléas, collected before 1854 (as part of the Salvandy-Fortoul survey). This version is almost identical to (a). - (e) "Son ar c'hemener", melody collected before 1913 in Ploëzal by François Vallée, reproduced, with 1 Vannes dialect variant of "Kalz a amzer" in "Musiques Bretonnes" by Maurice Duhammel (songs 412 and 413, p. 210). The lyrics are those collected by Luzel. - (f) "Zon ar c'hemener" in the "Soniou Breiz-Izel" by F-M. Luzel (T.2, pp.234-237), collected before 1880 at Plouëc de Trieux. - (g) "Pa 'c'ha' r c'hemener d'he labor" collected in 1890-1909 at Penvenan by Anatole Le Braz. (Quoted by Tanguy in "Anatole Le Braz et la tradition Populaire en Bretagne", 2, 63). - (h) "Ar c'hemener" collected in 1989 (CD record), then in 1995 in Trédarzec by Ifig Le Troadec, published in "Carnets de route", 2005 with musical notation. The background sound on this page alternates the two melodies published by Maurice DuhammeL. About the lyrics: In the argument ushering in the song "The Dwarves" in the 1839 Barzhaz, La Villemarqué suggests explanations for the execration of the tailors expressed here with such nastiness: "This class [was formerly] doomed to ridicule, in Brittany ... and elsewhere, ... among all wazrlike nations, whose hectic and wandering lives did not fit well with a home-like and peaceful existence." That said, the contempt that the peasants felt towards the tailor was fueled by several sources:

The same stanza exists in the song Loiza I , stanza j, on page 257 of La Villemarqué's notebook N° 1. It should have been used for an additional Barzhaz song, "La Quenouille", but for the untoward intervention of Luzel. There is an even more humiliating variant to this curse:

It was undoubtedly Lédan's broadside sheet which mostly helped the theme of the tailor as scum of mankind to spread and become popular tradition. However, neither of the broadside he published and his ms song mentions his name, as was usual for the texts he wrote. Lédan has probably copied an old folk song or synthesized several existing versions. This is confirmed by the presence of a verse of "The Tailor" in "The Swan", a song probably relating to an event dating back to 1379. We may surmise that the version recorded by La Villemarqué, judging by its peculiar elements, "fart in a cushion", "stealing scraps of cloth", "feeding from a pig trough", is independent of the Lédan version. Perhaps it was recorded even before the said Lédan version ... |

"Ar hemener", 16ème leçon de "Deskom Brezoneg" de V. Seité et L. Stéphan

|

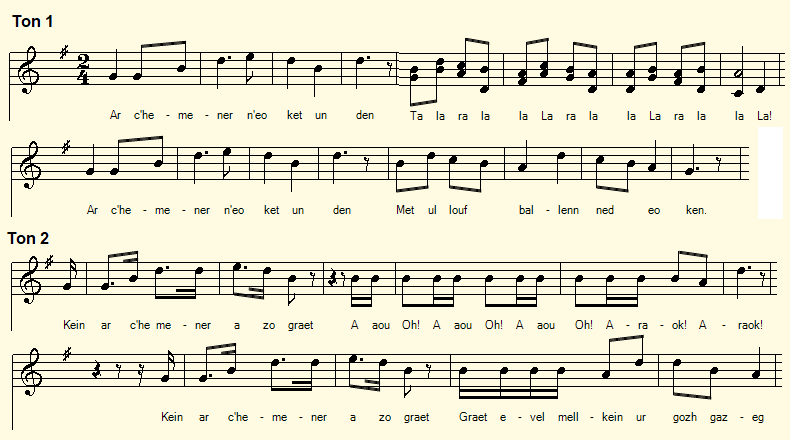

BREZHONEK page 88 Ar c'hemener - Kemeneur ---- 1. Ar c’hemenour n'eo ket un den, Talaralala laralala laralala la Ar c’hemenour n'eo ket un den, Met ul louf-ballenn ned eo ken 2. Kein ar c’hemener a zo graet, Evel mell-kein ur gozh gazeg 3. Pa ya ar c’hemenour da wriat A ya en ti mat bennak. 4. Ray 'met kanañ ha c’hwitellat, Tenno pezhoù d'eus ar wiad. 5. Tamm d'eus homañ, tamm d'eus eben: Setu savet ul liñsel wenn. 6. Hag o tresoù ha venviachoù, Evit ober brezel d’al laou. 7. Ur c’hemener n'eo ket un den Met ur brocher-c'hwen ned eo ken 8. Ar c'hemener ne verit ket Ne verit ket bout interet , 9. Ne verit ket bout interet Talaralala laralala lalala arc'hoazh E-barzh an douar benniget. 10. Met en tu bennak en douar kerc'h, Aaou! oh! Aaou! oh! Aou! Araok! Araok! Ha chas ar c’harter war e lerc'h. p. 89 / 46 11. An diveradur d'eus ar gwez D’ober dour benniget war e vez. 12. Ar c’hemenour ne merit ket, Kaout ur skudell d’ober e voued 13. Nemet e laouerig ur pemoc’h Ar c’hemenourig, respet d’eoc’h! KLT gant Christian Souchon |

TRADUCTION FRANCAISE page 88 Ar c'hemener - Kemeneur ---- 1. Le tailleur n'est pas un humain, Talaralala laralala laralala la Le tailleur n'est pas un humain Mais il n''est rien qu'un pet dans un coussin. 2. Le tailleur qui fait le gros dos Une vieille jument, en moins beau 3. Quand pour coudre vient le tailleur C'est pour un bon logis un malheur: 4. Il chante et siffle, rien de plus Met de côté des bouts au tissu. 5. Un bout par ci, un bout par là: De quoi composer tout un drap. 6. Ses instruments servent surtout A faire une âpre guerre aux poux. 7. Et le tailleur n'est rien de plus, Ma foi, qu'un embrocheur de puces. 8. Le tailleur ne mérite point D'être enfoui parmi les chétiens. 9. Il ne mérite d'être enfoui Talaralala laralala lalala demain Dans un sol qu'un prêtre a béni. 10. Mais dans un champ d'avoine, ah oui , Aaou! oh! aou! aoh! aou! arao! arao! Où les chiens du quartier l'ont suivi. p. 89 / 46 11. L'égout des arbres sera l'eau, L'eau bénite arrosant son tombeau. 12. Le tailleur ne mérite pas Une écuelle pour son repas. 13. Mais une auge pour les cochons! Sauf votre respect, mon garçon"! Traduction: Christian Souchon (c) 2020 |

ENGLISH TRANSLATION page 88 The tailor ---- 1. The tailor is not a human Talaralala laralala laralala la The tailor is not a human But he's but a fart in a cushion. 2. A tailor's back from neck to croup Looks like an old mare's back: a bad stoop 3. The tailor who comes in to sew On a decent home he brings great woe: 4. He whistles and he sings his fill. Steal away scraps of fabric, he will. 5. Just a bit here, just a bit there: A whole sheet soon he will have to spare. 6. His needle is his own device To wage bitter war against the lice. 7. The tailor he is nothing more Than a damned flea-skimmer on the floor. 8. The tailor he does not merit In a Christian ground to be buried. 9. The tailor does not have to rest Talaralala laralala at the best In a soil that by a priest was blessed. 10. No, but somewhere in an oats field, Araow! Araow! Araow! Woof! Woof! From which neighbourhood's dogs will not yield. p. 89/ 46 11. The rain that drips down from the leaves Be the holy water on his grave. 12. And he does not deserve a real And true earthenware bowl for his meal. 13. Let us him have th' trough for the pig, With all due respect, and not too big! " Translated by Christian Souchon (c) 2020 |