La prophétie de Gwenc'hlan

Gwenc'hlan's prophecy

Dialecte de Cornouaille

|

"Nous n'avons entendu [ce chant] qu'en Cornouaille. Cependant il doit être aussi connu dans le nord le la Basse Bretagne où M. de Penguern a recueilli plusieurs fragments poétiques attribués au même barde." (édit. 1839 p.19) "[Ce chant] m'a été chanté dans la paroisse de Melgven, par un mendiant appelé Guillou Ar Gall" ("Argument" de l'édition 1845). "Chant recueilli en Melgven ..." (édition de 1867 p. 18) Bien qu'ayant fourni à elle seule 9 chants: Prophétie de Gwenc'hlan, Enfant supposé , Les Nains , Merlin le Barde , Retour d'Angleterre, Epouse du Croisé , Frère de lait , La Fontenelle , Meunière de Pontaro , Annaïk Le Breton a été oubliée par Mme de La Villemarqué lorsqu'elle a dressé sa première liste de chanteurs, la Table B, la seule qui fut prête à temps pour que son fils pût s'en servir pour préparer l'édition de 1845. Il a suppléé à cet oubli en se fiant à sa mémoire, sans doute moins fidèle que celle de sa mère. "Clémence Penquerc'h [ fille de Marie-Jeanne Droal, dite Mélan, épouse Penquerh de Penanros en Nizon], se souvient très bien de ... la Prédiction de Guiclan" (écrit la nièce du Barde, Camille de La Villemarqué (1855 - 1945) à son cousin Pierre, le 21.11.1906 ). Cette Clémence mourut en 1908, sans que personne ne soit allé la voir. Camille écrit dans la même lettre que la fille unique d'Annaïk le Breton était encore en vie et qu'elle irait l'interroger. Il doit s'agir de sa petite fille. |

GUINCLAN dans les "Notices" de Miorcec (1818) et dans le "Dictionnaire" du Père Grégoire (1732) |

"We heard [this song] in Cornouaille. However it should be known also in the Northern part of Lower Brittany, where M. de Penguern has collected several fragments of poetry ascribed to the same bard." (édit. 1839 p.19) "[This song] was sung to me in the parish Melgven, by a beggar named Guillou Ar Gall" ("Argument", 1846 edition). "Song collected at Melgven..." (1867 Edition, p.18) Though she was the informer for 9 songs, Gwenc'hlan's prophecy, The changeling, The Gnomes , Merlin the Bard , Return from England, The Crusader's Wife , The Foster-Brother, La Fontenelle , The Pontaro Miller's Wife, Annaïk Le Breton was forgotten by Mme de La Villemarqué when she set up her first list of singers, Table B, the only list which her son could refer to when preparing the 1845 edition of the Barzhaz. He made up for this omission by relying on his own memory which was apparently less reliable than his mother's. "Clémence Penquerc'h [daughter of Marie-Jeanne Droal alias Mélan, wife of Penquerh, from Penanros near Nizon], remembers very well the 'Prediction of Guiclan'" (so wrote the Bard's niece, Camille de La Villemarqué (1855 - 1945) to her cousin Pierre, in a letter dated 21.11.1906 ). This Clémence died in 1908, but it did not occur to anybody to go and ask her questions. Camille also states in the same letter that Annaïk Le Breton's only daughter was still alive and that she would go and ask her. She must have meant her grand-daughter. |

|

Camille se trompe lorsqu'elle écrit "J"ai bien connu la vieille Annaïk Le Breton, morte il y a une vingtaine d'années" [donc vers 1887]. Elle a dû connaître sa fille, car Annaïk est décédée en 1839 et Camille est née en 1855. Alors que Camille "connaissait toutes les familles, parlait admirablement breton ... et resta jusqu'à la fin de sa vie [en 1945], d'une vitalité étonnante, personne... ne vint jamais la questionner", note D. Laurent (p.285 des "Sources"). |

Camille is very likely mistaken when she writes: "I did know well old Annaïk Le Breton who died a score of years ago" [i.e. around 1887]. In fact, she must have known her daughter, since Annaïk died in 1839 and Camille was born in 1855. Concerning Camille, D. Laurent remarks on page 285 of the "Sources", "though she knew all families in the neighbourhood, spoke an excellent Breton ... and her mind remained quick and agile until the day she died, no one thought of asking her." |

|

On peut s'étonner de voir assimilés ci-après, les aspects les plus divers d'un personnage supposé unique: le Gwenc'hlan du Barzhaz, le Guinclan des dictionnaires, le Vieil aveugle (an Den kozh dall) de la collection De Penguern, le Gwynglaff du Chant royal, le Gwenc'hlan des Contes du soleil et de la lune d'Anatole Le Braz, le Gouinclé de Torgen-ar-Sal. Si j'avais des scrupules à faire un tel amalgame je n'en ai plus: Le site https://to.kan.bzh qui propose une base de données relative aux chansons de tradition orale (TO) en langue bretonne consignées dans les livres, revues et manuscrits et qui utilise la classification élaborée par le fondateur et ancien président de l'association Dastum, Patrick Malrieu, présente sous le même n° M-00252 et le même titre critique "Diougan Gwenc'hlan" 4 séries de pièces: A: le chant de La Villemarqué; B: le Vieil aveugle de Penguern; C: des prophéties collectées par Hippolyte Raison du Cleuziou (1819-1896), archiviste de la Société archéologique des Côtes-du-Nord. Elles ont été communiquées par son petit-fils à l'érudit celtisant Gwennolé Le Menn qui les a rapprochées du Chant Royal et d'autres sources, dont les propos de l’octogénaire, Mme Le Corre rapportés dans un ouvrage du régionaliste Ernest Le Barzic intitulé "Merveille de la côte de Granit Rose. L’Île-Grande Enez-Veur et ses environs" (Rennes, 1970). D: des formules proverbiales (Lavaroù kozh) extraites des archives dudit Du Cleuziou; au total, 8 versions et 19 occurrences. Ces rapprochements mettent en évidence dans toutes ces sources un corpus commun de "formules prophétiques" ayant trait à des sujets précis. Un "livre de Guinclan" est évoqué par plusieurs d'entre elles. Voir aussi Dialog de Guynglaff et Er roe Stevan Voici la prophétie suivie de quelques proverbes tirés des manuscrits Du Cleuziou: |

We may wonder if merging together the most diverse aspects of a supposedly unique character makes sense: the prophet Gwenc'hlan of Barzhaz, the Guinclan of the dictionaries, the Old blind man (an Den kozh dall) of the collection De Penguern , the Gwynglaff of the "Royal Song", the Gwenc'hlan of the "Tales of the Sun and Moon" by Anatole Le Braz, the Gouinclé from Torgen-ar-Sal. I found that this amalgam was already made: The website https://to.kan.bzh offers a database of Breton oral tradition (TO) songs recorded in books, journals and manuscripts. Using the classification developed by the founder and former president of the Dastum society, Patrick Malrieu, it presents under the same number M-00252 and the same critical title "Diougan Gwenc'hlan" 4 series of pieces: A: the song of La Villemarqué; B: the old blind man of Penguern; C: prophecies collected by Hippolyte Raison du Cleuziou (1819-1896), archivist of the Côtes-du-Nord Archaeological Society; They were communicated by his grandson to the Celtic scholar Gwennolé Le Menn who compared them with the Royal Song and other sources, including the words of the octogenarian, Mrs.Le Corre reported in a book by the local historian Ernest Le Barzic entitled "A wonder of the Red Granite Coast. the Île-Grande aka Enez-Veur" (Rennes, 1970). D: proverbial formulas (Lavaroù kozh) extracted from the Du Cleuziou archives; in total, 8 versions and 19 occurrences. These comparisons highlight in all these sources a common corpus of "prophetic formulas" relating to specific subjects. A "Guinclan book" is mentioned by several of them. See also Dialog of Guynglaff and Er roe Stevan Here is the prophecy followed by a few sayings taken from the Du Cleuziou ms collection: |

|

1 Eürus, eürus vo ar bed Pa zigouezo Loeiz C’hwezek. E buhez avat na bado ket. Un amzer a vo gwelet 5 E vo an dud ken disgizet Ha na vo ket anavezet Dilhad ar peizantezed Dimeus ar re dimezelled. Erruout a rayo ar giz 10 Ma vezo an dud gwisket en brizh: Ar kapichonoù a vo lakaet Ar pantalonoù a vo gwisket Maleürus a vezo ar bed Pa vo an dud gwisket evel naered. (1) 15 Amzer a vo e vo gwelet An hañv, ar goañv kemmesket Ken ne vont ket anavezet Nemed d'eus ar gwez deliaouek Hag ar gouelioù instituet. 20 Amzer a vo a vesterdien a gonduo ar bed, Ar fallañ dud gwellañ dimezet. Ar fallañ dud gwellañ estimet. An togoù kolet a vo lakaet. Ar mibien a essañs mat a yelo da c'hlask o boued. 25 Amzer a vo e vo gwelet Brezel en Frañs hag a vo kalet, Brezel sivil ha brezel all Lec'h ma vo chefoù priñsipal. Hag en amzer-se en-em daolo an dud fall war ar Roue hag en-devo kalz a boan en-em tenn, mar ra. Henchoù a vo graet a-dreuz ar parrezioù da gonduiñ d’an aod. Er komañsament evo mestroù pere n'eo ket fall outo e ve labouret warne. Mes goude e vo chañjet: ar mestroù a ray o anvañs mat. Ha ne vint ket peurechuët Ma vo fin d'ar boulversamañt. Eüruz a vo an hini Pehini en-devo e ti 30 Etre Vilemoan ha Gindi (1) Ma hell diwall eus ar bleizi Ha dimeus an degouidi. A la fin pa vo bet brezeloù en pep fason e vo lavaret: peoc'h vo bremañ. Mes allas! Souden goude e truyo seizh rouantelezh war ar Frañs hag a formo un arme a tri-ugent lev a-hed hag a daou-ugent lev a lec'hed. Hag a dalc'ho da avañs ken a vint rentet en Menez-Bre. Eno e aretint hag a bep kostez a erruo ar maerioù gant o farosioù, gwazed ha merc'hed a redont hep goût petra a reont da redek. Ha pa vint erru eno, e vo savet daou enseign: unan fall hag unan vat. Ar Roue komañs ar kombat pehini a yelo er kostez ma garo. Neuze e vo ur kombat ken sanglant ma hellfe div vilin o valañ gant ar gwad epad daou devezh. Ma gounid an hini vat e vo friket ar c'hostez fall Ne chomje hini anezhe. Mar gounid an hini fall e vo lezenn fin ar bed, hep esperañs ebet Mar gounit an hini mat, e teuio ar peoc'h Hag ar tranquillité da ren er bed; Da vihannañ ur pennad. (1) Velimoan est une petite île ou rocher sur cette côte-ci. |

1 Heureux sera le monde Jusqu'à ce qu'arrive Louis XVI. Sa vie longtemps ne durera pas. Un temps viendra où l'on verra 5 Que les gens seront si déguisés Qu'on ne distinguera plus Les vêtements des paysannes De ceux des demoiselles. Il arrivera la mode 10 Des gens vêtus en bariolé. On portera des capuchons Ainsi que des pantalons. Malheureux sera le monde Quand les gens seront vêtus comme des serpents. 15 Un temps viendra où l'on verra L'été et l'hiver confondus, Au point qu'on ne les distinguera Que par les arbres porteurs de feuilles Et par les fêtes instituées. 20 Un temps où des bâtards mèneront le monde, Où les pires gens seront les mieux mariées Les pires gens les mieux estimées. On portera des chapeaux collés Les fils des meilleures familles iront mendier. 25. Un temps viendra où l'on verra L'âpre guerre faire rage en France. Guerre civile et autre guerre Opposant les principaux chefs. En ce temps-là les gens méchants se jetteront sur le roi qui aura beaucoup de mal à s'en tirer, s'il y arrive. Des chemins seront faits à travers les paroisses, conduisant au rivage. Au commencement il y aura des maîtres lesquels ne voudront pas qu'on y travaille. Puis tout changera; Leurs chantiers iront bon train . A peine seront-ils achevés que ce sera la fin du bouleversement. Heureux celui Qui habitera 30 Entre La Méloine (1) et Le Guindy, S’il peut se défendre des loups et des nouveaux arrivants. A la fin, quand il y aura eu des guerres de toutes sortes, on dira: il nous faut la paix désormais.Hélas, aussitôt après, sept royaumes se rueront sur la France: une armée de 60 lieues de long et 40 de large qui avancera sans s'interrompre jusqu'au Ménez-Bre. Là elle s'arrêtera et de tous côtés afflueront les maires et leurs communes, hommes et femmes accourant sans en savoir la raison. Et quand ils seront arrivés là , on dressera deux enseignes, celle du mal et celle du bien. Alors eclatera un combat où chacun choisira son camp. Et il sera si sanglant que le sang versé pourrait alimenter deux moulins pendant deux jours. Si le camp du bien l'emporte, celui du mal sera anéanti et il n'en restera plus rien. Si c'est le mal qui l'emporte, s'imposera la loi de la fin du monde sans espérance aucune. Si c'est le bien, la paix et la tranquilité règneront sur terre, du moins pendant un moment. (1) Velimoan est une petite île ou rocher sur cette côte-ci. |

1 Happy will be the world when Louis XVI comes, his life will not last. A time will come when we see 5 People so disguised That you no longer an tell the clothes Of peasant women From those of young ladies. Fashion will come of 10 People dressed in colorful clothes: They will wear hoods As well as trousers. Unhappy people that will Be dressed in snake hides. 15 A time will come when we see Summer and winter merge together So that you won't tell one from the other, But for the leaf-bearing trees And the feasts and holidays. 20 A time when bastards will lead the world, Where the worst people will be best married And best considered. They will wear "glued" hats The sons of the best families will go beg. 25. A time will come when we see The bitter war raging in France. Civil war and other war Opposing the main leaders. In those times wicked people will assault the king who will have much trouble getting away, if ever he can escape. Paths will cut through the parishes, leading to the shore. At first rulers will be reluctant to work on them. But at a later stage ther will be a dramatic change. These projects will thrive. No sooner will they be completed than the upheaval will come to an end. Happy whoever Will live 30 Between La Méloine (1) and the Guindy river If he can defend himself from wolves and new comers. Eventually, after all sorts of wars, we will say: we need peace from now on. Alas, immediately afterwards, seven kingdoms will rush onto France: an 60 leagues long and 40 leagues wide army will move on inexorably as far as Ménez-Bre. There they will stop and from all sides will flock the mayors and their communes, men and women running driven wilde. And there, two standards will be erected, that of evil and that of good. There will be a fight and evryone will have to choose their side. And it will be so bloody a fray that the blood spilled could drive two mills for two days. If the good party wins, the evil party will vanish and nothing will be left of it. If the evil party prevails, the law of Armageddon will be instored forever. If the good men carry the day, peace and tranquility will reign on earth, at least for a while. (1) Velimoan is a small island or rock on this coast. |

|

Pa vez an delioù war ar bodenn Kement ha divskouarn ul logodenn Tle adverenn war wenojenn Ar ran a gan kent miz Ebrel A zo gwelloc’h dezhañ tevel Pa zeu ‘n avel tu Roch-al-Lazh James buoc’h kozh d'an ebaz ‘N hini n’eus ket c’hoant kaout naon Na chom ket re bell war e skaon. Gwasoc’h eo un taol teod Eget un taol kleze. h.a. Bevañ, mervel, zo memez tra Digant Doue vit nep a ya. |

Quand les feuilles du buisson sont aussi longues que l’oreille d’une souris, Le goûter doit se faire sur le chemin des champs. La grenouille qui chante avant avril ferait bien de se taire. Quand le vent vient du côté de Roc’hellas, jamais vieille vache ne prend ses ébats. Qui ne veut sentir la faim, ne doit pas rester longtemps sur son siège. Un coup de langue fait plus de mal qu’un coup d’épieu. Etc…. Vivre, mourir, sont une même chose pour celui que Dieu accompagne. |

When the leaves of the bush are as long as the ear of a mouse, We must have our lunch on our way to the fields. The frog who sings before April would do well to shut up. When the wind blows from the side of Roc'hellas, No old cow should be left alone . Who does not want to feel hungry, Should not stay too long in his seat. A tongue may cause a lot of pain Much more than a shot of a spear. Etc .... To live, to die, are the same thing To whom God accompanies. |

|

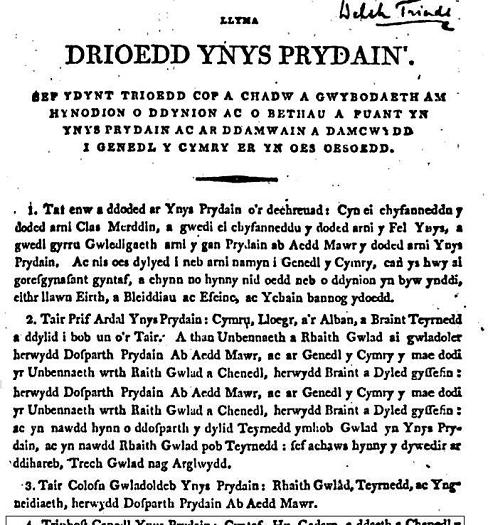

Dictionnaire français-celtique ou fançais-breton nécessaire à tous ceux qui veulent apprendre à traduire le français en celtique ou en langage breton, pour prêcher, catéchiser et confesser, dans les différents dialectes de chaque diocèse... Rennes, 1732, chez J. Vatar. A gauche, exemplaire commun portant l'inscription: "Ex dono Josephi Francisci Dandigné, le 23 Germinal an 5e ou le 12 avril 1797," suivi des signatures "Desnos" et "Desfosses", ainsi que d'un tampon plus récent: "C. J. de Laroche". A droite, exemplaire relié en maroquin rouge, dentelles, aux armes de la reine Marie Leszczynska. H. 26 cm; L. 21 cm. Versailles, Bibliothèque municipale - Rés. F132 Joseph-François Dandigné de la Chasse, né à Rennes le 29 janvier 1724, fut sacré évêque de Léon le 11 août 1763, nommé à l'évêché de Chalon en 1772, il donna sa démission en 1781.Il fut également comte de Chalon-sur-Saône et Conseiller du roi en tous ses conseils. Il mourut en 1807. |

French-Celtic or French-Breton dictionary necessary for all those who want to learn to translate French into Celtic or into Breton language, to preach, catechize and confess, in the different dialects of each diocese ... Rennes, 1732, at J. Vatar's. On the left, a common copy bearing the inscription: "Ex dono Josephi Francisci Dandigné, 23 Germinal year 5 or 12 April 1797, " followed by signatures "Desnos" and "Desfosses", as well as a more recent stamp: "C. J. de Laroche". On the right, a copy bound in red morocco, lace, with the arms of Queen Marie Leszczynska. H. 26 cm; L. 21 cm. Versailles, Municipal Library - Res. F132 Joseph-François Dandigné de la Chasse, born in Rennes on January 29, 1724, was consecrated bishop of Léon on August 11, 1763, appointed to the bishopric of Chalon in 1772,.He resigned in 1781. He was also count of Chalon- sur-Saône and the King's Counselor in all His councils. He died in 1807. |

Ton

(Fa dièse mineur, after the arrangement by Friedrich Silcher)

| Français | English |

|---|---|

|

1. Le soleil sombre en l'océan, Sur mon seuil, on entend mon chant. 2. J'étais jeune et chantais alors; Je suis vieux, mais je chante encor. 3. Chantant le jour, chantant la nuit, Je chante et mon cœur est meurtri. 4. Tête baissée, plein d'affliction: Mon chagrin n'est pas sans raison. 5. Ce n'est certes pas que j'aie peur; Et j'attends la mort sans frayeur. 6. Je n'ai pas peur assurément; J'ai vécu bien assez longtemps. 7. Tu cherches et ne me trouves pas; Sans chercher, tu me trouveras. 8. Qu'importe ce qu'il m'adviendra, Car ce qui doit être sera. 9. Mourir trois fois c'est notre lot Avant notre éternel repos. 10. Hors du bois le vieux sanglier Sort en boitant, le pied blessé. 11. De sa gueule ouverte le sang S'écoule et son crin est tout blanc. 12. Autour de lui ses marcassins Grognent, car ils ont tous grand faim. 13. Le cheval de mer que je vois, Le rivage en tremble d'effroi. 14. Comme neige blanche brillant, Il porte au front cornes d'argent. 15. On voit sous lui bouillonner l'eau Au feu tonnant de ses naseaux. 16. D'autres chevaux il vient autant Qu'il y a d'herbe au bord d'un étang. 17. - Cheval de mer, frappe-le donc A la tête! Frappe et tiens bon! 18. Les pieds nus glissent dans le sang. Frappe fort, frappe constamment! 19. Le sang monte comme un ruisseau! Frappe donc encore, il le faut! 20. Le sang monte jusqu'au genou! Comme un lac il s'étend partout! 21. Frappe plus fort! Et frappe bien! Tu te reposeras demain. 22. Frappe-le, cheval des tempêtes, Frappe-le fort! Frappe à la tête! - 23. Dans ma tombe froide endormi, J'entendis l'aigle dans la nuit 24. Lancer aux aiglons son appel Et à tous les oiseaux du ciel. 25. Il disait dans son âpre chant: - Prenez votre envol, vivement! 26. Chairs pourries de brebis, de chien Ne valent la chair d'un Chrétien! - 27. - Vieux corbeau de mer, O, dis-moi, Dans tes griffes, que tiens-tu là? 28. La tête du Chef exécré A laquelle il faut arracher 29. Ses deux yeux rouges, car jadis A toi-même c'est ce qu'il fit. 30. - Et toi renard, viens et dis-moi: Dans ta gueule que tiens-tu là? 31. - C'est son cœur sournois que je tiens; Un cœur aussi faux que le mien. 32. Il avait médité ta mort Et t'infligea ton triste sort. 33. - Dis-moi, crapaud, pourquoi tu couches, Embusqué tout près de sa bouche? 34. - Il faut que je demeure ici Pour happer au vol son esprit. 35. Rester en moi ma vie durant, Ce sera là le châtiment 36. De son crime envers le poète D'entre Port Blanc et Roche Verte . -" NOTE: Italiques: Passages inspirés de la littérature galloise (Aneurin "Y Goddodin": str. 1, 20; Llyvarch Hen "Canu Heledd, Ystafell Cynddylan": str. 2, 23 à 26; Taliesin "Tri chylch hanfod..." : str. 9, 13) ou de références bretonnes (str.26 et 36) - Caractères gras: Mots commentés par F. Elies-Abeozen. trad.Ch.Souchon (c) 2008 |

1. When the sun sets and the seas swell, I sing by the house where I dwell. 2. Did I as a youth sing my fill? No, I am old and I sing still. 3. I sing by night, I sing by day, Though I am distressed and at bay. 4. I have, aye, for complaint a ground. I bend my head and I am downed. 5. Not nearing death gives me a scare. They may kill me: I do not care. 6. I feel neither terror nor fright; I have lived as long as I might. 7. They may try to find me: they won't; But they will find me if they don't. 8. I don't care about time to come: When time is ripe I shall succumb. 9. Three times have gone through death all those Who enjoy eternal repose. 10. I see a boar, out of the wood Limping his way, with injured foot, 11. With open, bleeding mouth, at bay. With his hair by old age turned grey, 12. And his young wild boars walk in front. They are hungry, they snort and grunt. 13. Now, a seahorse is drawing near: The whole shore quivers out of fear. 14. His white coat dazzling all over, On his head two horns of silver. 15. The waters boil below him from His nose's thundering blaze and scum. 16. Other seahorses are around, Like reeds on a pond they abound. 17. - Stand fast! Stand fast! Stand fast, sea horse! Hit him on the head with high force! 18. Naked feet slip on blood you spill. Harder your blows! Aye, harder still! 19. Out comes a brook of pouring blood! Hit harder to increase the flood! 20. I see him stay in blood, knee-deep! Let him in a pond of blood creep! 21. Now, hit harder! Hit and stand fast! You may rest when the day is past! 22. Hit on, hit on horse of the sea On the head! As hard as can be! 23. I was asleep in my cold grave: I heard the eagle for help crave: 24. He called his eaglets from his lair, And all birds and fowls of the air. 25. And in his call he kept saying - Hasten, hasten, birds on the wing! 26. Of dog or sheep no rotten flesh You shall have, but Christian's and fresh! - 27. - O Cormorant, cormorant, say, What is the thing with which you play! 28. - The Chieftain's skull: I am about Both of his red eyes to gouge out; 29. Out of the sockets red blood pours: He has done once the same with yours. 30. - Now, tell me fox with your red claws, What is it you hold in your jaws? 31. - It is his heart that I could seize 'Cause my heart is as false as his 32 Who hatched a plot, hastened your death And has made you breathe your last breath. 33. - Tell me, toad, what do you wait for, Crouching here on his mouth's shore? 34. - He is dying and I stay there To catch his soul gasping for air. 35. It shall dwell in me, mixed with mine, Till I die, atone for his crime 36. Against the Bard whose home once was Between Porzh-Gwenn and Roc'h-al-Lazh.-" NOTE: Italics: Passages inspired by Welsh literature (Aneurin "Y Goddodin": str. 1, 20; Llyvarch Hen "Canu Heledd, Ystafell Cynddylan": str. 2, 23 à 26; Taliesin "Tri chylch hanfod..." : str. 9, 13) or by Breton tradition (str.26 et 36) - Bold characters: words commented by F. Elies-Abeozen. transl.Ch.Souchon (c) 2008 |

Cliquer ici pour lire les textes bretons.

For Breton texts, click here.

|

Résumé C'est avec ce chant que s'ouvrait la première édition du Barzhaz, celle de 1839, avant qu'il ne soit "supplanté" par les "Séries" en 1845. Gwenc'hlan est un barde qu'un prince chrétien retenait prisonnier après lui avoir crevé les yeux. Ayant le don de prophétie, il prédit qu'il sera vengé par un prince païen. C'est la vision d'un sanglier blessé (le prince chrétien), entouré de ses marcassins qu'un cheval de mer blanc aux cornes d'argent (le prince païen) vient frapper furieusement, répandant une mare de sang. Autre vision: le barde est couché dans sa tombe. Il entend l'aigle appeler ses aiglons et tous les oiseaux du ciel pour venir se repaître de chair chrétienne. Un corbeau est occupé à arracher ses deux yeux rouges de la tête du chef de guerre qui a emprisonné et fait aveugler le poète. Un renard déchire son cœur hypocrite. Quant à son âme, elle ira habiter le corps d'un crapaud. Contrairement à la pièce précédente, ce poème n'a jamais été collecté par d'autres que La Villemarqué. La plupart des folkloristes, en particulier Francis Gourvil qui découvrit en 1924 un "Chant Royal" dont l'existence était annoncée par deux auteurs du XVIIIème siècle, considèrent le "Gwenc'hlan" du Barzhaz comme une forgerie fabriquée par le jeune chartiste à partir de réminiscences littéraires, en particulier galloises. Ces dernières deviennent pour lui une référence de prédilection après sa participation à l'"eisteddfod" de 1838 à Abergavenny. Un examen attentif de ce "Chant Royal", du poème du Barzhaz et des commentaires qui l'accompagnent, d'une lettre de la nièce du Barde, Camille de La Villemarqué, ainsi que d'un texte d'un autre de ses détracteurs habituels, Anatole Le Braz, conduisent à réviser ce jugement péremptoire et à conclure, même s'il est absent des manuscrits de Keransquer, à l'existence possible, sinon probable d'un authentique poème populaire à l'origine de ce texte magnifique. Le Guinclan des dictionnaires En 1834 les érudits bretons s'intéressaient à un mystérieux manuscrit: "les prophéties de Guinclan" (Guiclan ou Guinclaff) considéré comme disparu, depuis la Révolution, de l'abbaye bénédictine de Landévennec où, au dire du linguiste Dom Le Pelletier et du Capucin Grégoire de Rostrenen, il était conservé autrefois. Tous deux auteurs de dictionnaires bretons, ils avaient, l'un fait des citations, l'autre mentionné l'existence de ce texte. Gwinglaff est effectivement cité à trois reprises dans ce dictionnaire: - aux mots "bagad" ("troupe") Le pluriel est 'bagadou' qui se trouve pour 'des troupes dans les Prophéties de Gwinglâf, qui prédit:

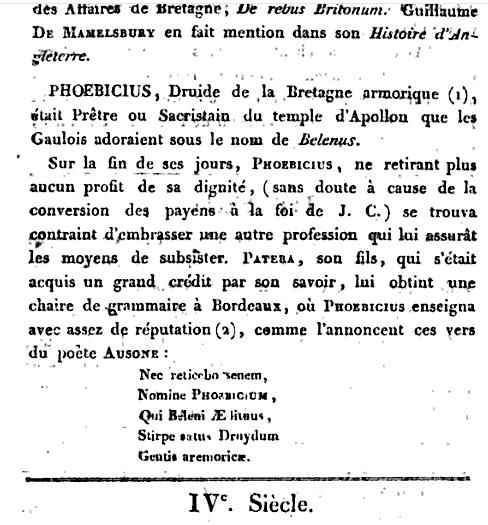

-et "orzail" , (="batterie", corruption, dit Le Pelletier du français "assaillir") 1° Dans l'introduction: Liste des...auteurs dont je me suis servi pour composer ce dictionnaire: "Ce que j'ai trouvé de plus ancien sur la langue... bretonne a été le livre manuscrit en langue bretonne des Prédictions de Guinclan, astronome breton très fameux encore aujourd'hui parmi les Bretons qui l'appellent communément "le Prophète Guinclan". Il marque au commencement de ses prédictions, qu'il écrivait l'an de salut deux cent quarante (240), demeurant entre Roc'h-Hellas et le Porz-Gwenn: c'est au diocèse de Tréguier, entre Morlaix et la ville de Tréguier" 2° A l'article "Guinclan", page 480 du dictionnaire qui comporte plusieurs noms propres: "Guinclan, prophète breton, ou plutôt astrologue qui vivait dans le 3ème siècle, [et] dont j'ai vu les prédictions en rimes bretonnes à l'abbaye de Landévennec entre les mains du R.P. Dom Louis Le Pelletier.". Sa lecture ne dut pas être très attentive, car il ajoute: "[Il] était natif de la comté de Goélo en Bretagne armorique [la région qui s'étend de Paimpol à Saint-Brieuc] et prédit aux environs de l'an de grâce 240, (comme il le dit lui-même), ce qui est arrivé depuis dans les deux Bretagnes [dans la traduction bretonne de l'article: 'en Armorique et en Grande Bretagne']." La contradiction avec le futur dictionnaire de Dom Le Pelletier dut lui être signalée, peut-être par ce dernier, car 6 ans plus tard, dans sa "Grammaire Celto-Bretonne" (1738), il la corrige partiellement: "Il s'est glissé...dans mon Dictionnaire...une très grosse [erreur]: C'est au mot Guinclan dont j'ai marqué les prédictions à l'an 240 au lieu qu'il faut mettre 450." 3° Notons, pour être complet que le mot "prédiction", page 749, contient le renvoi (Voyez Güinclan), article qui contient effectivement la traduction proposée ici "diougan". Le Guinclan de Miorcec de Kerdanet C'est surtout le cas de Daniel-Louis Miorcec de Kerdanet dans ses "Notices Chronologiques..." (1818) où l'on peut lire (pp. 8-9): "L'avenir... entendra parler de Guinclan. Un jour les descendants de Brutus [= les Bretons] élèveront leurs voix sur le Ménez-Bré. Ils s'écriront en regardant cette montagne: 'Ici habita Guinclan'. Ils admireront les générations qui ne sont plus, et les temps dont je sus sonder la profondeur." La Villemarqué a repris cette phrase de confiance dans la "Bibliographie bretonne" de Levot (1852). Il est aisé de démontrer qu'il s'agit -là d'une paraphrase de la "Guerre de Carros", tirée de la traduction par Le Tourneur d'"Ossian, fils de Fingal" de McPherson: "L'avenir entendra parler d'Ossian. Un jour les descendants du lâche élèveront leurs voix sur Cona. Ils s'écrieront en regardant ce rocher: 'Ici habita jadis Ossian'; ils admireront et les générations qui ne sont plus et les héros que j'ai chantés." "Ma'z marvint holl a strolladoù War Menez Bré, a bagadoù." C'est-à-dire: "Qu'ils mourront tous par bandes Sur Ménez-Bré, par troupes." Cette citation est tirée du mot "Bagad" du Dictionnaire de Le Pelletier, p.33, où il est seulement dit que le pluriel "bagadoù" pour "des troupes" se trouve dans les Prophéties de Gwinglâf". Lesdites "Prophéties", redécouvertes en 1924, s'intéressent effectivement avant tout au sort de Guingamp entre 1570 et 1588. Mais dans ce document, les troupeaux humains qui périssent sur le Ménez-Bré (à 20 km de Guingamp) sont les Bretons enrôlés de force par les Anglais. La Villemarqué, quant à lui, citera la même phrase en l'appliquant aux prêtres catholiques. Hag an dud diskilhet..."

C'est donc, plus que le père Grégoire et son erreur de date, Miorcec de Kerdanet qui est le grand responsable de toute la fantasmagorie autour du fameux prophète du Vème siècle qui enflamma tant d'imaginations et en particulier celle du jeune La Villemarqué. La soi-disant découverte de La Villemarqué Comme on le verra à propos du premier chant qu'il publia, "la Peste d'Elliant", le jeune chartiste avait eu en 1835 un entretien avec Miorcec à sa résidence de Lesneven. Il fut certainement question dans leur conversation du mystérieux prophète, car, dans le post-scriptum de la lettre qu'il lui envoya le 20 septembre, il lui demandait: Francis Gourvil, l'auteur d'une volumineuse étude publiée en 1960 sur "La Villemarqué et le Barzaz-Breiz", voit dans le silence du jeune La Villemarqué la preuve d'une duplicité précoce... Dans une lettre, sans doute du premier semestre de 1835, Mme de La Villemarqué écrit à son fils: Réponse du recteur en janvier 1836: "...Jamais notre fabrique n'a possédé ce fameux manuscrit et tout ce que les journaux ont débité à ce sujet n'est qu'un tissu d'erreurs...On a confondu la vie de Sainte Nonne, patronne de la paroisse avec les œuvres de votre compatriote..." (La vie de Sainte Nonne, "Buhez Santez Nonn" fut publiée en 1837 par l'Abbé Sionnet avec une traduction du grammairien Le Gonidec. Ces lettres sont citées par F. Gourvil dans la "Nouvelle Revue de Bretagne", numéros de mai et juillet 1949) La polémique avec Mérimée Une entrevue eut lieu entre les deux hommes en janvier 1836 qui mit fin en apparence à l'incident. Mais on peut supposer que le franc-parler de Mérimée ne manqua pas de blesser profondément l'amour propre et la fierté du jeune Breton. Mérimée se vengea en publiant un rapport,"Notes d'un voyage dans l'ouest de la France", où il reproche aux Bretons, en dépit de leur patriotisme provincial, de n'être pas préoccupés par la sauvegarde de leurs monuments et expose qu'il appartient au gouvernement de prêcher l'exemple. Cette polémique où s'exacerba le nationalisme local du jeune homme, a nuit à sa carrière débutante, en prévenant contre lui des écrivains de renom: Sainte-Beuve qui le premier met en doute "l'exactitude...de ses recherches...et l'esprit critique qui y aurait présidé", et Lamartine dont il ne reçut jamais que de vagues encouragements. Ayant essuyé un refus de la part de la "Revue des Deux- Mondes", créée en 1830, il fait paraître dans l'"Echo de la Jeune -France", le 15 mars 1836, un article intitulé Un débris du bardisme accompagné du chant La Peste d'Elliant qu'il datait du 6ème siècle. Cet article répond aux agressions verbales de Mérimée et contient "tout le Barzaz Breiz en puissance", comme l'a écrit le linguiste F. Gourvil. On y trouve en effet des envolées lyriques telles que: "Aujourd'hui qu'asservis à la France et privés de notre liberté, nous avons cessé de former une nation à part..." ou "La France, cette étrangère qui est venue s'offrir à nos pères un poignard à la main, et qui nous oppresse et nous tue! Non, non, ô ma Bretagne...nous n'aurons de mère que toi, nous voulons mourir sur ton sein!" Ces déconvenues se poursuivirent jusqu'à ce que La Villemarqué trouve dans l'historien Augustin Thierry et son ami, Claude Fauriel de l'Institut, des partisans enthousiastes de ses travaux. Thierry insère en effet, en 1838, dans la 5ème édition de son "Histoire de la conquête de l'Angleterre", le chant Retour d'Angleterre, en ajoutant que ce "curieux morceau de poésie... est destiné à faire partie d'un recueil intitulé "Barzaz Breiz" dont la publication aura lieu prochainement." Cependant, l'organisme public sollicité, le "Comité historique de la langue et de la littérature françaises", refusa de cautionner la publication du "Barzhaz" objectant "l'impossibilité...d'en constater la date, l'origine...et combien il serait fâcheux pour le Comité de couvrir de son crédit la fraude de quelque McPherson inconnu." (L'auteur des poèmes d'Ossian qui avait perdu toute crédibilité depuis longtemps). Le Gwenc'hlan gallois de La Villemarqué Le 30 avril 1838 La Villemarqué était missionné par le Ministère de l'Instruction publique pour participer en octobre au congrès celtique dit "Eisteddfod" d'Abergavenny au Pays de Galles. La perception qu'il eut désormais du mystérieux prophète se ressentit, tout comme l'ensemble de son œuvre, de ce contact prolongé avec la culture cambrienne (cf. encart ci-après). A titre de justification, il indique que des écrivains anglais modernes, l'historien Sharon Turner et Evan Evans, le traducteur de "Y Gododdin" admettent de telles approximations pour les poètes gallois Aneurin et Llyfarc'h Hen! Signalons que dans un article publié dans les "Annales de Bretagne", 1930, vol. 39-1, page 30, Emile Ernault rapproche ce nom de "Gwengolo" (Paille Blanche) qui désigne le mois de Septembre. La plus récente remarque que j'aie trouvée à ce sujet explique "Gueinth Guant" par "Gwenith Gwawd" qui signifierait "Froment (breton "gwinizh") de Louange". Le même Taliésin, en parlant d'un chef gallois, l'appelle le "cheval de guerre" (str. 13). et le même poème offre un vers qui se retrouve presque littéralement dans le chant armoricain : «On voit une mare de sang monter jusqu’au genou." (str.20) Une tradition apocryphe? Il est peu probable que le jeune La Villemarqué ait créé ex nihilo un texte d'une telle puissance évocatrice. permet à Villemarqué de présenter son héros comme ayant un double aspect: barde guerrier et agriculteur. Cette assimilation lui a sans doute été inspirée par ce qu'il affirme, à tort, être une autre citation de Dom Le Pelletier (mais qu'il a trouvée chez Kerdanet):

Cette double source recoupe l'indication fournie par le Père Grégoire dans l'introduction de son Dictionnaire (Liste des auteurs dont je me suis servi pour composer ce dictionnaire): Il n'est pas plus indulgent pour des modifications de détail introduites, tantôt pour se conformer aux règles de Le Gonidec: la disparition du double archaïsme "and erc'h gann" (la neige blanche, mot féminin, strophe 14), remplacé par "an erc'h kann" (forme moderne masculine précédée de l'article usuel); l'imparfait "me a gane" au lieu du conditionnel "me ganefe"; avec un "e" intercalaire, tantôt pour créer de nouvelles allitérations: "Pa" (quand), répété 4 fois dans les stophes 1 et 2, au lieu de "Ma" (si). C'est le même souci de l'allitération qui le conduit à transformer la strophe 15: Gant an tan gurun euz he fri. qui devient: An dour dindanañ o virviñ Gant an tan daran eus e fri. ainsi que la strophe 14: En ken gwenn ewid an erc'h gann. qui devient: Eñ ken gwenn evel an erc'h kann, alors que, s'il s'en était tenu aux règles édictées par Le Gonidec, il aurait écrit: Eñ ker gwenn evit an erc'h kann, dont toute allitération aurait disparu. Jubainville n'aurait certainement pas consacré plus de la moitié (près de 8 pages) de son étude à un texte qu'il aurait considéré comme une simple forgerie à laquelle on pouvait toucher sans inconvénient. C'est pourquoi, on ne saurait considérer à coup sûr ce chant comme apocryphe, même si, à n'en pas douter, il a été sérieusement "retravaillé" par le collecteur, selon son habitude. Le Gwenc'hlan des Romantiques En 1852 l'Abbé Daniel plaçait Guinclan sur le rocher "où le barde Gwenc'hlan maudit tant de fois le christianisme naissant dans nos contrées... [On] a fait dernièrement ériger une croix sur la pointe de Roc'h Allaz: c'est encore un démenti de plus donné aux prédictions de Gwenc'hlan" (Bibliothèque bretonne, Saint-Brieuc II, p.761). La même conception se retrouve sous la plume d'Anatole de Barthélémy dans ses "Mélanges historiques sur la Bretagne", I, 1853, p.58 et Benjamin Jollivet dans sa "Géographie des Côtes-du-Nord", IV, 1859, p.123 Les deux dictons "barbares" Comme on l'a dit à propos du "Gwenc'hlan gallois", La Villemarqué n'était pas en reste et citait, lui aussi, "Gwenc'hlan selon Kerdanet" dès la première édition du Barzhaz de 1839 (pp. xi, xii et 11): Dans l'édition de 1839, on rappelle aux lecteurs de "L'histoire de la langue des Gaulois" qu'une tradition dans ce sens est "rapportée par M. de Kerdanet", mais cette précision ne figure plus aux éditions suivantes et, On trouve un équivalent français de cette phrase dans le "Guyonvarc'h" de Dufilhol (Paris, 1835, pp.26, 109 et 163): "Arrose, arrose ton moulin, il veut tourner avec du sang". R. Largillière considérait en 1925 qu'on avait là un centon qui existe encore dans la bouche des paysans du Bas-Tréguier. L'authenticité de cet aphorisme semble confirmée par une communication du grammairien François Vallée au congrès de Moncontour de l'"Association Bretonne", en 1912, qui affirma avoir recueilli une "prophétie rimée" sur la résurrection de Guinklan, sur le combat terrible qui doit se livrer et sur "le moulin de l'Île Verte qui tournera avec du sang". Cette affirmation est accueillie avec le plus grand scepticisme par Francis Gourvil en 1960 dans son important ouvrage déjà cité. Le Gwynglaff du "Dialogue avec le roi Arthur" En 1924, ce même Francis Gourvil (1889 - 1984) découvrit dans le grenier du manoir de Keromnès, en Locquénolé, près de Morlaix, à l'occasion d'un partage de bibliothèque, un manuscrit contenant 247 vers intégralement copiés par Dom Le Pelletier lui-même constituant la fameuse prophétie, sous le titre "Dialog etre Arzur, Roe an Bretounet ha Gwynglaff" (Dialogue entre Arthur, roi des Bretons et Guinclan), suivi des mots "L'an de Notre Seigneur Mil quatre cent et cinquante". Un copiste mal avisé avait raturé le mot "mil" (ce qui explique l'erreur du père Grégoire), mais, pour critiquer cette rature, le savant Dom Pelletier attirait l'attention sur les mots français dont ce texte est truffé, au nombre desquels on trouve "canol" pour "canons". Le texte de ce "Dialogue" où Guiclan ne figure pas comme auteur, mais comme acteur, est structuré comme suit, selon l'analyse publiée par R. Largillière dans les "Annales de Bretagne" (tome 38, 1929): 1° Vie de Gwynglaff, être à demi sauvage, n'ayant d'autre abri que les arbres des forêts dans lesquelles il errait couvert d'une cape rousse. Il connaissait l'avenir. (c'est le thème de l'"homme sauvage" que l'on retrouve dans le chant Merlin Barde). 2° Un dimanche, le roi Arthur [une référence antique qui, elle aussi, excuse Grégoire de Rostrenen] se saisit de lui et lui intime l'ordre assorti de menaces de lui dire quels prodiges arriveront en Bretagne avant la fin du monde. 3°Réponse: "Tu sauras tout, excepté ta mort et la mienne" suivie de précisions difficiles à interpréter; été et hiver confondus, jeunes gens à cheveux gris, la pire terre qui fournit le meilleur blé [ce qui confirme l'affirmation de La Villemarqué]; hérétiques défiant la loi divine, etc. 4° Prédictions concernant les années de 1570 à 1575 et 1587 et 1588. 5° Longue réponse à une question du roi: guerres et destructions imputables aux seuls Anglais. Sous peine d'être décapités, les Bretons sans armes et les gens armés devront affronter les ennemis. Ils mourront par bandes et par troupes sur le Ménez Bré; devront assiéger Guingamp, rompre ses murailles et piller ses biens. On violera les filles, tuera hommes et femmes. Par punition de Dieu, les Saxons prendront possession de la Bretagne. Les passages en caractères gras avaient été cités par divers auteurs avant la redécouverte du manuscrit. D'autres sont cités dans les deux dictionnaires qui s'en inspirent, mais sont absents du manuscrit: le mot "orzail" (Le Pelletier) et la phrase indiquant que Guinclan "demeurait entre Roc'h-Hellas et le Porz-Gwenn" (Grégoire). Sur le manuscrit, Dom Le Pelletier mentionne 2 versions des Prophéties. Ces mots doivent figurer sur la version manquante qu'il a montrée au Père Grégoire. Selon J. Tourneur-Aumont, dans les mêmes Annales, il s'agit d'un "Chant royal" composé suivant les canons en vigueur au XVème siècle pour servir les intérêts du roi de France Charles VII. L'intérêt de ce texte est philologique, non historique. F. Gourvil remarque que rien n'indique qu'il ait été la propriété de l'abbaye de Landévennec et rien n'autorise non plus à supposer qu'il ait été détruit sous la Révolution. Dans le "Que-sais-je?" qu'il consacre en 1952 à la "Langue et littérature bretonnes", le même Francis Gourvil souligne insidieusement, que, selon lui, cette découverte "a permis de réduire à néant les prétentions de ceux qui, croyant le texte disparu à jamais, avaient inconsidérément abusé de lui." Il est clair qu'il vise spécialement le poème publié par La Villemarqué. Il ressort, cependant, de ce qui précède, que ce dernier ne prétendait nullement avoir restitué les "prophéties" disparues, mais rendre compte d'une tradition orale. Loin d'infirmer les affirmations du jeune Barde, cette pièce les confirme:

Le Gwenc'hlan d'Anatole Le Braz On a vu à propos des Séries que La Villemarqué avait en Anatole le Braz un critique acerbe. Et pourtant, dans les "Contes du Soleil et de la Brume" (1905) du même Le Braz, on trouve une description très poétique du Ménez-Bré, cette "montagne" de 300 m à l'ouest de Guingamp, dont il assure que: Le Braz ne rechigne pas à citer les trois premières strophes du Barzhaz, lorsqu'il évoque "la plainte amère que lui a prêtée, dans le Barzaz-Breiz, le vicomte de La Villemarqué." Il poursuit: "Dans toute l'ancienne Domnonée [côte nord de la Bretagne], ses prédictions étaient célèbres. Elles furent même rédigées par écrit et l'on en conservait, paraît-il, un recueil, il y a quelque deux cents ans, chez les moines de Landévennec. Aujourd'hui, ce n'est guère que dans la mémoire du peuple que l'on peut trouver un écho fort affaibli de ces paroles sibyllines, de ces 'diou-ganoù'". La source de cette tradition orale relative au prophète n'est autre que Marguerite Philippe, ou Marc'harid Fulup, (1837 -1909). Aussi appelée Godik ar Vognez (Margot la Manchote), c'était l'informatrice principale de Luzel, à Plouaret et elle lui enseigna à elle-seule 259 chants. En l'occurrence, il s'agit de contes relatifs au mystérieux personnage: Une tradition similaire est évoquée par M. Le Teurs dans le "Bulletin de la Société Archéologique du Finistère" (1875-1876, p.179). Elle concerne la paroisse de Saint-Urbain dans le Finistère, où un tertre nommé "Torgen ar Sal" est réputé être la sépulture de "Gouinclé". Il y repose avec ses trésors. L'interprète habituel de Marguerite Philippe, François-Marie Luzel n'a jamais entendu parler de Gwenc'hlan, si ce n'est, dit-il, qu': "A Louargat, au pied du Ménez-Bré, une vieille femme que j'interrogeais m'a dit un jour qu'il y avait autrefois ur Warc'hlan sur le sommet de la montagne. Serait-ce une altération de Gwinglaff? Elle ne savait du reste si c'était un homme ou un animal". La conclusion que tire R. Largillière de ce qui précède dans son étude sur Gwenc'hlan, c'est que "les créations littéraires des écrivains du XIXème siècle ont pénétré dans le peuple" et que, loin de rapporter fidèlement, comme il l'affirme, les paroles de Marguerite Philippe, Anatole Le Braz a beaucoup enjolivé son récit. C'est d'autant plus probable, selon lui, que dans un article de "La Plume" du 1er mars 1894, il écrivait: "Qui de nous n'eût aimé à se représenter comme réel ce grand spectre bardique...sur la cime solitaire du Ménez-Bré? [comme l'a fait La Villemarqué] ...Mais la critique sérieuse en doit faire son deuil. Je ne m'y résigne pas sans regret". Le Braz aurait-il, onze ans plus tard, succombé au mirage et commis envers la muse populaire les mêmes indélicatesses que celles qu'il se plait à reprocher à La Villemarqué? On peut en douter. Le Barzhaz Breizh: un mauvais livre? En 1960, F. Gourvil devient plus catégorique et soutient une thèse à l'université de Rennes, publiée plus tard sous le titre révélateur: "L'authenticité du Barzaz Breiz et ses défenseurs à la rescousse d'un mauvais livre". Puis en 1966, il critique, de façon peut-être plus justifiée, "La langue du Barzaz Breiz et ses irrégularités". Ces positions excessives sont largement infirmées par les travaux de M. Donatien Laurent. Ce musicien et linguiste découvrit en 1964 au manoir de Keransquer, près de Quimperlé, propriété de la famille de La Villemarqué, les carnets de collecte de ce dernier. Conclusion Il doit en être de cette "diougan" (prophétie) comme des autres chants mythologiques et historiques anciens du Barzhaz. Elle unit à une magnifique mélodie authentique, des mots, La source du chant dont se souvenait Clémence Penquerc'h était-elle le Barzhaz-Breizh lui-même? De l'avis de Donatien Laurent,: "[On] admettra difficilement qu'un chanteur illettré et monolingue retienne justement du recueil cette pièce marginale si différente de ton et d'inspiration de celles de son répertoire habituel [et que, de plus,] la Dame de Nizon, elle aussi, mentionne" (comme chantée par Annaïk Le Breton). En tout état de cause, on ne peut que regretter, comme le fait Donatien Laurent, que personne ne soit " allé voir Clémence Penquerc'h, fille de la Marie-Jeanne des tables qui n'est morte qu'en 1908!" Même si la "Prophétie de Gwenc'hlan" est en partie une œuvre autonome, créée par La Villemarqué, en faisant appel à des souvenirs livresques, pour les besoins de ses diverses causes, on ne peut qu'admirer l'extraordinaire force d'évocation poétique de cette pièce. Les qualités de ces textes "d'imagination" sont pour beaucoup dans l'engouement suscité par le "Barzhaz Breizh" dans toute l'Europe: on trouvera ici une paraphrase de la "Marche d'Arthur" et la traduction du début de la "Prophétie de Gwenc'hlan" publiée en 1912 en NEERLANDAIS. Note: Outre "Aux Sources" de Donatien Laurent, une grande partie des développements ci-dessus est tirée de l'ouvrage de Francis Gourvil, "Théodore de La Villemarqué et le Barzaz-Breiz" (1960) qui n'est autre que sa thèse de doctorat. L'autre source principale est l'article "Gwenc'hlan" publié par R. Largillière in: "Annales de Bretagne, Tome 37, numéros 3-4, 1925. pp. 288-308. |

Résumé It was with this song that the first 1839 edition of the Barzhaz opened, before it was "superseded" by the "Series" in 1845 . Gwenc'hlan is a bard whom a Christian prince held captive after he had gouged out his eyes. Having a gift for prophecy, he predicts that he will be avenged by a Pagan prince. He has a vision: a wounded boar (the Christian prince) accompanied by its young which a white sea horse (the Pagan prince) furiously hits with its silver horns, shedding a pool of blood. Another vision: the bard lies in his grave. He hears the eagle calling its eaglets and all the birds of the sky that they may feed on Christian flesh. A raven is endeavouring to peck out the two red eyes off the head of the Christian chieftain who had imprisoned the bard and gouged out his eyes. A fox tears his hypocrite heart to pieces. As for his soul, it is doomed to don the body of a toad. Unlike the previous piece, this poem never was collected by anybody but La Villemarqué. Most folklorists, especially Francis Gourvil who discovered in 1924 a "Chant Royal" whose existence was stated by two 18th century authors, look on the Barzhaz ballad "Gwenc'hlan" as on a forgery composed by the young scholar in combining bookish reminiscences, in particular Welsh Bardic poetry. These Wesh poems became his favourite references as a consequence of his partaking in the 1838 "eisteddfod" at Abergavenny. But anyone pondering on this "Chant Royal", on the Barzhaz poem and the comments accompanying it, on a letter penned by the Bard of Nizon's niece, Camille de La Villemarqué, as well as an essay by one of his usual disparagers, Anatole Le Braz, will be led to reconsider their opinion and to admit that, even if it is missing in the Keransquer MSs, genuine lore possibly, if not very likely existed whereon this inspiring epic poem is based. The Guinclan of the dictionaries In 1834 many Breton scholars were in search of a mysterious MS: "Guinclan's prophecies" (or "Guiclan" or "Guinclaff") which was considered lost when the Benedictine abbey of Landévennec was destroyed by the Revolution. Now it was formerly kept there, according to two linguists, the Reverend Le Pelletier and the Capucin monk Gregory of Rostrenen. Both of them had composed Breton dictionaries where they respectively quoted excerpts from this document, or mentioned its existence. Gwinglaff is really quoted three times in this dictionary: - under the items "bagad" ("party"), The plural is 'bagadou' which translates 'lots of people' in Gwinglâf's Prophecies that announce:

- and "orzail", (="battery", a corrupted word derived, so says Le Pelletier from the French "assaillir"). 1° In the Introduction: List of authors used to compose this dictionary: "The oldest document in Breton language I found was the hand-written Breton Predictions of Guinclan, a Breton astronomer who is still very famous among today's Bretons who usually refer to him as 'Prophet Guinclan'. He states at the beginning of his Predictions that he wrote in the year of grace two hundred forty (240), when he was dwelling between Roc'h-Hellas and Porz-Gwenn, in the bishopric Tréguier, between Morlaix and Tréguier town". 2° Under the item "Guinclan", on page 480 of the dictionary that includes several proper nouns: "Guinclan a Breton prophet or, more precisely, an astronomer who lived in the third century, whose predictions in Breton verse I saw, at Landévennec Abbey, in the hands of the Reverend Dom Louis Le Pelletier." Apparently, he did not peruse it intently, since he added: "He was born in the County Goélo [the area between Paimpol and Saint Brieuc], and had foretold around the year of grace 240 (as he asserts himself) whatever was to change and to happen since then in "both Brittanies" [i.e. Brittany and Britain, as stated in the Breton version of his note]." He must have been aware of the contradiction with Dom Pelletier's future dictionary, since, 6 years later, he partly corrected this statement in his "Celto-Breton Grammar" (1738): "A gross mistake has crept into my Dictionary, concerning Guinclan whose "Predictions" I have dated to the year 240, instead of the year 450". 3° For the sake of exhaustiveness be it said that the item "prediction", on page 479, includes the prompt (See Güinclan). The latter item contains the same translation for "prediction", namely "diougan". Miorcec de Kerdanet's Guinclan So did above all the local historian Daniel-Louis Miorcec de Kerdanet in his "Chronological notices" (1818) where he writes on pages 8-9: La Villemarqué quoted this sentence, on trust in the "Bibliographie bretonne" edited by Levot (1852). It is easy to prove that this is a mere paraphrase of "The Carros War", which is part of a translation by Le Tourneur of McPherson's "Ossian, son of Fingal": "Times to come shall hear of Ossian. Some day the Coward's offspring shall raise their voices on the hills of Cona. And they shall cry, looking at these rocks: 'Here was once Ossian's dwelling'; and they shall marvel at the folks of yore and the heroes I celebrated." "Ma'z marvint holl a strolladoù War Menez Bré, a bagadoù." meaning: "That they will die, the lot of them, On the Ménez Bré, whole legions." This quotation will be found under the word "bagad" in Le Pelletier's dictionary, page 33, with the bare mention that the plural "bagadoù" meaning "legions" occurs in "Gwinlâf's Prophecies". These "Prophecies", rediscovered in 1924, really address above all the future of Guingamp between 1570 and 1588. But in this document, the human flocks that will be slaughtered upon the Ménez-Bré (20 km west of Guingamp) are Bretons who were forcibly enlisted by the English. La Villemarqué will quote the same sentence but consider it applies to the priests of Christ. Hag an dud diskilhet..."

Much more than Father Gregory and his erroneous dating, it was, consequently, Miorcec de Kerdanet who was accountable for the wild imaginings that throve about the famous prophet of the fifth century. They inspired in particular young La Villemarqué. An alleged discovery by La Villemarqué As mentioned on the page dedicated to the first song he ever published "The Plague in Elliant", the young scholar had in 1835 an interview with Miorcec at the latter's house in Lesneven. The both certainly evoked in their discussion the ghostly prophet, since La Villemarqué asked in a post-scriptum to the letter he sent to his friend on 20th September: Francis Gourvil who recounts these proceedings in his stately book on "La Villemarqué and the Barzaz-Breiz", published in 1960, considers the silence of the young man on that occasion as a proof of his precocious malice... In a letter dated to the first semester 1835, Mme de La Villemarqué wrote to her son: Answer of the curate in January 1836: "...Never did our fabric have the famous document in their possession and all that was poured forth by newspapers about it is false... They have mistaken the "Life of Saint Nonn", the patron saint of our parish, for the works of your fellow countryman... (The "Life of Saint Nonn", "Buhez Santez Nonn" was published in 1837 by the Reverend Sionnet along with a translation by the Grammarian Le Gonidec. Both letters are quoted by F. Gourvil in "Nouvelle Revue de Bretagne", issues of May and July 1949)). The argument with Mérimée An interview between the two men in January 1836 apparently put an end to the controversy. But it is likely that Mérimée's outspokenness did not fail to deeply hurt the young Breton's self-esteem and national pride. Mérimée avenged himself by blaming the Bretons, in a report titled "Account of a trip to Western France", for neglecting the upkeep of their heritage and he urged the government to preach by example. This argument, not only exacerbated the young man's regional jingoism, but greatly harmed his career at its very outset, as it biased against him some renowned writers like Sainte-Beuve who was the first author questioning "the accuracy... of his research methods... and wondering if he applied a critical mind to them", and Lamartine who favoured him with but non-committal encouragements. Since the already famous "Revue des Deux Mondes" (created in 1830) had refused it, it was in the "Echo de la Jeune -France" that, on 16th March 1836, his article titled Bardic Remains was published, to which the ballad The Plague of Elliant, dating back, in his opinion, to the 6th century A.C. was attached. It is an answer to Mérimée's verbal brutality. "It contains in embryo the whole Barzhaz Breizh" as Francis Gourvil rightly remarked. One may find in it flights of lyrical poetry like: "Today we are tied to France with abject bonds and deprived of the ancient liberties we used to enjoy as an independent nation..." or "France, this alien who imposed herself on our forefathers by wielding her dagger, and is still oppressing us and killing our children! No, no, O Brittany...we shall have no mother but you and die while protecting your breast!" These disappointments went on until La Villemarqué found in the historian Augustin Thierry and his friend Claude Fauriel of the Institute (the 5 French Academies) enthusiastic supporters of his works. Thierry inserted, in 1838, into the 5th edition of his "History of the conquest of England", the song Back from England, and he adds that "this curious relic of poetry... is intended to be included in a a collection titled "Barzaz Breiz" to be published very soon." However, the public body approached, the "Historical Committee on French language and literature", refused to sponsor the publishing of the book, objecting that "it was impossible... to trace the date and origin of the songs... and that it would not be convenient for the Committee to cover with their authority the forgery of a new McPherson." (McPherson, the author of "Ossian" had not yet, like now, partly recovered his long lost credibility). La Villemarqué's Welsh Gwenc'hlan On 30th April 1838, La Villemarqué was chosen by the Ministry of Education to take part in a Celtic congress, the so-called "Eisteddfod" of Abergavenny (Wales). His perception of the mysterious prophet was thoroughly influenced, as well as the whole of his work, by this prolonged contact with the Welsh culture (See insert below) By way of justification he invokes the modern English authors, the historian Sharon Turner and Evan Evans, the translator of "Y Gododdin", who indulge in such assimilations concerning the Welsh poets Aneurin and Llyfarch Hen! Another interpretation is given in a study published in "Annales de Bretagne", 1930, vol. 39-1, page 30, by Emile Ernault who parallels this name with "Gwengolo" (White straw), which applies to the month September. The most recent relevant note I found explains "Gueinth Guant" as "Gwenith Gwawd" which would mean "Wheat (Breton "gwinizh") of Praise". These strange translations have disappeared in the 1867 edition. Now I am Taliesin" (see stanza 9). The same Taliesin, referring to a Welsh chieftain calls him "war steed" (st. 13). and the same poem has a verse that appears almost unchanged in the Breton song: "There will be a spate of blood, a flood wherein we shall stand knee-deep" (st. 20). Is this spurious folk lore? One may maintain that such inspiring lyrics are unlikely to have been created ex nihilo by young La Villemarqué. enables him to make of his hero both a bard-warrior and a soil tiller. Maybe he was prompted to this assimilation by an alleged quotation of Dom Pelletier (which he found in one of Kerdanet's books):

Country folks name it 'Gwenc'hlan's Prediction'. It displays This coincids with the Reverend Gregory's statement in the introduction to his Dictionary (List of authors used to compose this dictionary): They usually refer to him as 'the Prophet Guinclan'" Therefore we must not needs consider this song as a spurious fiction, even if the genuine original was thoroughly "trimmed" as was apparently the collector's wont. He is no more lenient for petty changes intended to conform the text with Le Gonidec's grammar rules: he removed the double archaism "and erc'h gann" (the white snow, a feminine word, stanza 14), replaced by "an erc'h kann" (the modern masculine noun preceded by the usual article; the imperfect "me a gane" (I sang) instead of the old conditionnal "me ganefe" (I would sing), with an inset "e". Another reason is the wish to create additional alliterations: "Pa" (when), repeated four times in stanzas 1 and 2, instead of "Ma" (if). The same wish for alliterations prompted La Villemarqué to rewrite stanza 15: Gant an tan gurun euz he fri. becomes: An dour dindanañ o virviñ Gant an tan daran eus e fri. Similarly stanza 14: En ken gwenn ewid an erc'h gann. becomes: Eñ ken gwenn evel an erc'h kann, whereas, if he had only respected the rules set forth by Le Gonidec, he would have written: Eñ ker gwenn evit an erc'h kann, in which no alliteration is left. Jubainville would cetainly not have dedicated over half of his study(almost 8 pages) to a text he had considered a mere fake that could be tampered with without inconvenient. Therefore we must not needs consider this song as a spurious fiction, even if the genuine original was thoroughly "trimmed" as was apparently the collector's wont. The romantic authors and Gwenc'hlan In 1852 Abbé Daniel assigned Guinclan his stand on the rock "where Bard Gwenc'hlan so oft called a curse on the Christian faith that was spreading over our country...A cross was recently erected on Roc'h-Allaz point: another refutation of Gwenc'hlan's soothsaying" ("Bibliothèque bretonne", Saint-Brieuc II, p.761). The same views are expressed by Anatole de Barthélémy in his "Miscellanies on Breton History", I, 1853, p.58 and Benjamin Jollivet in his "Geographic description of the Département Côtes-du-Nord", IV, 1859, p.123. Two "barbarous" sayings As stated in connection with the "Welsh Gwenc'hlan", La Villemarqué followed this example and quoted "Gwenc'hlan revisited by Kerdanet" as from the first 1839 edition of the Barzhaz (pp. xi, xii et 11): In the 1839 edition, the readers of Kerdanet's "History of the language of the Gauls" were reminded of a passage with the same meaning quoted by this author, but this precision is missing in the later editions and "Rod ar vilin a valo flour / Gand goad ar venec’h eleac’h dour." (The wheels of the mills shall grind fine with blood of monks instead of water).» A similar sentence (in French) could be found in Dufilhol's "Guyonvarc'h" (Paris, 1835, pp.26, 109 and 163): "Soak, soak your mill. It wants to spin in blood". R. Largillière in "Annales de Bretagne", book 37, N°3-4, p.300, in 1925, considered it a bit of Lower-Trégor folk doggerel. The genuineness of this phrase is apparently guaranteed by the grammarian François Vallée who read a paper at the 1912 meeting of the "Association Bretonne", in Moncontour, to the effect that he had collected, as he said, "rhymed prophecy" about Guinklan's coming back to life, the terrible combat that will take place and "the mills on Green Island that shall be driven by streams of blood". This statement is met with extreme scepticism by the author, in 1960 of the afore-mentioned "La Villemarqué and the Barzaz-Breiz", Francis Gourvil. The Gwynglaff in the "Dialogue with King Arthur" In 1924, the linguist and writer, Francis Gourvil (1889 - 1984) discovered in the attic of a manor at Locquénolé, near Morlaix, following the sale by auction of a book collection, a handwritten poem consisting of 247 lines in Dom Le Pelletier's handwriting, composing the famous prophecy and titled "An dialog etre Arzhur, Roue d'an Bretounet ha Guynglaff" ( A Dialogue between Arthur King of the Bretons and Guinclan), followed by the words "In the year of grace A thousand four hundred and fifty". The original copyist was ill-advised enough to cross out the words "a thousand" (which accounts for the Reverend Gregory's mistake) but, to blame this erasure Dom Pelletier hinted at the many French words in the text, for instance the word "canol" (cannon). This "Dialogue" where Guinclan is not mentioned as the author but as a protagonist is made up as follows according to the description made by R. Largillière in the "Annals of Brittany" (Book 38, 1929): 1° Life of Gwynglaff, a half-wild being who has no other dwelling than the trees in the forests where he roams clad in a reddish cloak. He can foretell the future. Consequently he is a figure similar to the "wylde man" depicted in the song Merlin the Bard. 2° One Sunday, King Arthur [an ancient reference contributing to explain Gregory of Rostrenen's error] captured him and ordered him under threat to unveil what misfortunes were to befall Brittany until Doomsday. 3° Answer: "You shall know all except the date of your death and mine" followed by statements impossible to elucidate: summer and winter merging together; hoary youngsters; worst soil yielding the best wheat [confirming La Villemarqué's assertion]; heretics challenging the law of God, etc. 4° Predictions for the years 1570 to 1575 and 1587- 1588. 5° A lengthy answer to the king's question: wars and destructions for which the sole English are blamed. Threatened to be beheaded, weaponless and armed Bretons alike will have to combat enemies. They will die, lots of them, on the Ménez Bré, whole legions; they will have to besiege Guingamp, pull down its walls and plunder its goods, rape the girls and slaughter men and women. As a punishment inflicted by God the Saxons shall take possession of Brittany. The phrases in bold characters were quoted by several authors even before the MS was rediscovered. Others are included in the two dictionaries drawing on them, but were not found on the MS: the word "orzail" (Le Pelletier) and the sentence to the effect that Guinclan "dwelt between Roc'h-Hellas and Porz-Gwenn" (Gregory). On the manuscript, Dom Le Pelletier mentions 2 versions of the Prophecies. Maybe these words were included on the missing version which he had shown the Rev. Gregory. As stated by J. Tourneur-Aumont in the same "Annals", this poem is a "Chant royal" composed in accordance with standards set in the 15th century to serve the interests of the king of France, Charles VII. This text may be of philological but , by no means of historical value. F. Gourvil notes that there is no indication that it was Landévennec Abbey's property or that it was destroyed by the Revolution. In an epitome on "Breton Language and Literature" published in 1952, in the "Que sais-je? collection, F. Gourvil insidiously remarks that his discovery " made futile any new attempt by diverse authors who believed that this text was lost for ever, to ascribe to the old bard their own writings." It is evident that, in saying so, he hints at La Villemarqué. It is nonetheless evident that the latter never pretended he was reconstructing any of the lost "prophecies", only contributing a piece of oral lore. Far from invalidating the young Bard's statements, this piece corroborates them:

Anatole Le Braz' Gwenc'hlan As we saw on the Series page Anatole Le Braz was a severe critic of La Villemarqué's collection. Yet, in his "Tales of Sun and Mist" (1905) he wrote a very inspiring description of the Ménez-Bré, a 300 meter "mount" west of Guingamp which he assures: Le Braz does not jib at quoting the first three stanzas of the Barzhaz Breizh poem when he evokes "the bitter moan placed into his mouth, in his collection, by Viscount de La Villemarqué". He adds: "Throughout old "Domnonea" [the area along the North coast of Brittany], his predictions were well-known. They even were committed to writing and some of them were allegedly kept, two hundred years ago by the monks of Landévennec. Today it is only in the folk's memory that you may look for an albeit fading echo of the sibylline words of his 'diou-ganoù'". The source of the oral tradition about this prophet is none other than Marguerite Philippe alias Marc'harid Fulup (1837 -1909). Also known as 'Godik ar Vognez' (One-armed Maggie), she was Luzel's main informer at Plouaret and he learned of her singing over 259 songs. In the present case she conveyed tales about the mysterious character. and, like an owl, he could turn his head all the way round. Similar fictional stuff is reported by M. Le Teurs in the "Journal of the Finistère Archaeological Society" (1875-1876, p.179). It is about the parish Saint-Urbain in Finistère where a mound, named "Torgen ar Sal" is considered to be "Gouinclé's grave" where he rests with his treasures. The customary interpret of Marguerite Philippe, François-Marie Luzel, never heard of Gwenc'hlan. At the very most he could report: "At Louargat, at the foot of the Ménez-Bré, an old woman whom I asked told me once that there was in former times on top of the mount, ur warc'hlan. Was it an alteration of Gwinglaff? Besides, she could not say if it was a man or an animal." The conclusion drawn by R. Largillière from these elements in his study on Gwenc'hlan, is that "the literary fictions created by 19th century authors have pervaded the imagination of the country folks" and that, far from truly reporting, as he asserts he does, Marguerite Philippe's narrative, Anatole Le Braz embellished it a great deal. This is all the more probable, in his opinion, since in an article published in "La Plume" on 1st March 1894, he wrote: "Who had not loved to depict as part of genuine lore this great bardic spectre ... atop the lonely Ménez-Bré? [as did La Villemarqué] ...But a serious critic must kiss it goodbye. I don't resign myself to it without regret". Did Le Braz, eleven years later, really succumb to the mirage and inflict on the popular muse the dishonesty for which he used to reproach La Villemarqué ? One may doubt it. Is the Barzhaz Breizh: A "bad book"? In 1960 F. Gourvil becomes more peremptory and at Rennes University he submits an essay published later on under the revealing title: "The authenticity of the Barzaz Breiz :How its defenders try to rescue a bad book". Then, in 1966, he criticizes, maybe with some reasons, "The language of the Barzaz Breiz and its irregularities". This extreme disparagement is greatly invalidated by Mr Donatien Laurent's research work. This musician and linguist discovered in 1964 in Keransquer Manor, near Quimperlé, a mansion belonging to La Villemarqué's family, the latter's collecting notebooks. These documents clearly demonstrate Conclusion Like the other mythological and old-historical songs in the Barzhaz, this "diougan" (prophecy) very likely combines a splendid, authentic popular tune with lyrics, Was the ultimate source of the song remembered by Clémence Penquerc'h the Barzhaz itself? Donatien Laurent answers: "It won't be easily admitted that an illiterate and monolingual singer could, of all the pieces included in the collection, remember especially this one, quite different from her usual repertoire in tone and inspiration, which the Lady of Nizon also mentions (as sung by Annaïk Le Breton). When all is said and done, one can only regret, as does Donatien Laurent that "nobody thought of paying a visit to Clémence Penquerc'h, daughter of the Marie-Jeanne in the Tables, who was alive until 1908!" Even if "Gwenc'hlan's prophecy" is to a large extent a fiction, based on bookish reminiscences, created by La Villemarqué to serve his different purposes, this poem has a remarkable evocative strength. These intrinsic qualities were a capital factor in the enthusiasm aroused by the "Barzhaz Breizh" throughout Europe: here are, for instance, a free adaptation of "Arthur's March" and a translation of the first stanzas of "Gwenc'hlan's prophecy" published in 1912 in DUTCH. Note: Beside "Aux Sources" by Donatien Laurent, a great part of the explanations above are based on "Théodore de La Villemarqué et le Barzaz-Breiz" by Francis Gourvil (1968), a reprint of his doctoral thesis. The other main source is the essay "Gwenc'hlan" published by R. Largillière in: "Annales de Bretagne, Tome 37, # 3-4, 1925. pp. 288-308. |

Page 54 du Carnet 3: "Ar Menez Bré" Dessins de la main de La Villemarqué

|

La prophétie de Gwenc'hlan sur laquelle s'ouvrait le Barzhaz dans la première édition, celle de 1839, tient une place particulière dans le parcours personnel de La Villemarqué. Le modèle gallois La tradition des congrès d'artistes gallois remonte au moins au 12ème siècle. Le premier "Eisteddfod" d'envergure se tint à Carmarthen, en 1451. Le second, dont on ait gardé trace, à Caerwys, en 1568. Au fil du temps, le niveau exigé des compétiteurs à l'"eisteddfod" alla en se dégradant. En 1789, un "eisteddfod" fut réuni à Corwen où, pour la première fois, le public fut admis. Iolo Morganwg fonda le "Gorsedd Beirdd Ynys Prydain" (Haute session des bardes de l'île de Bretagne) en 1792, en vue de restaurer et remplacer l'ancien "eisteddfod". Le premier "eisteddfod" nouvelle manière se tint à Primrose Hill, près de Londres en Octobre 1792. Le mérite d'avoir établi des relations entre ce mouvement et les intellectuels de Basse-Bretagne revient à la Société biblique de Londres qui avait commandé à Le Gonidec une traduction bretonne de l'Ancien Testament. Celui-ci, dans une lettre du 4 février 1837, signala au Révérend Thomas Price, président de l'association culturelle galloise "Cymdeithas Cymreigyddion y Fenni" deux défenseurs zélés de la langue bretonne, le poète Brizeux et un "antiquaire très studieux", Hersart de la Villemarqué. Ces derniers furent aussitôt admis comme membres d'honneur de cette association, ainsi que Le Gonidec. Le jeune chartiste écrivit alors au président pour être admis à concourir, lors du prochain "eisteddfod" qui devait se tenir à Abergavenny, pour la rédaction d'un mémoire sur "l'influence des traditions galloises sur les littératures européennes". A l'appui de sa demande, il signalait qu'il avait recueilli un grand nombre de chants des bardes d'Armorique parmi lesquels, disait-il, certains remontaient au Vème siècle. Grâce à une de ses relations, le comte de Montalembert, pair de France, il obtint du ministre de l'Instruction publique une mission officielle assortie d'une allocation de 600 francs. Le départ de La Villemarqué et de six de ses amis eut lieu fin septembre 1838. La Villemarqué revint de l'"eisteddfod" de 1838 avec un "rapport sur la littérature du Pays de Galles", daté de mai 1839, où il soutient que les contes gallois qui ont servi de modèle à Chrétien de Troyes furent importés de Bretagne. Il y attire aussi l'attention du ministre sur l'intérêt d'assemblées telles que ces eisteddfods "comme soutien du vieux patriotisme... [contribuant] à maintenir une heureuse harmonie entre le pauvre et le riche... [Le peuple est attaché à une aristocratie qui] veut partager avec lui des biens plus précieux que les fruits grossiers de la terre". Admis dans "l'ordre des bardes de l'Île de Bretagne", il avait trouvé là-bas un modèle à suivre, dans les efforts entrepris par Owen Jones (1741-1814), un fourreur londonien également connu sous son de nom de barde, "Myvyr", pour publier entre 1801 et 1807 avec un ancien maçon devenu homme de lettres, Edward Williams (1747-1826) dit "Iolo Morgannwg" (Edouard de Glamorgan) et l'auteur d'un célèbre dictionnaire gallois-anglais, William Owen Pughe (1769-1835) les "monuments populaires de la patrie" sous le titre "Myvyrian Archaiology of Wales". Les références au "Myvyrian" sont innombrables dans le Barzhaz. La "Myvyrian Archaiology of Wales" (extraits de Mary Jones' Celtic Encylopedia) Ce fut l'un des premiers recueils imprimés de littérature galloise du Moyen-âge, constitué à partir de manuscrits divers, dont les "Quatre Livres anciens de Galles". C'est aussi la source où puisèrent de nombreux traducteurs de littérature galloise, jusqu'à la publication par J. Gwenogwryn Evans des "Editions diplomatiques des manuscrits de Galles".  Malheureusement la Myvyrian Archaiology accueillit aussi les manuscrits provenant de la collection de Iolo

Morgannwg, considéré alors comme une autorité en matière de littérature et de folklore gallois, mais que le 20ème siècle a démasqué comme un faussaire. Toutefois, toutes ses contributions n'étaient pas de sa fabrication.

Malheureusement la Myvyrian Archaiology accueillit aussi les manuscrits provenant de la collection de Iolo

Morgannwg, considéré alors comme une autorité en matière de littérature et de folklore gallois, mais que le 20ème siècle a démasqué comme un faussaire. Toutefois, toutes ses contributions n'étaient pas de sa fabrication.